The Game is a mind game in which the objective is to avoid thinking about The Game itself. Thinking about The Game constitutes a loss, which must be announced each time it occurs.

The programming version of The Game has the same rules, but you lose if you think about David Heinemeier Hansson (aka DHH).

And no, I'm not linking to why I lost today.

Broke a four-month winning streak, dangit.

If you rush and don’t consider how it is deployed, and how it helps your engineers grow, you risk degrading your engineering talent over time

—

I don't disagree that overreliance on AI could stymie overall growth of devs, but we've had a form of this problem for years.

I met plenty of devs pre-AI who didn't understand anything other than how to do the basics in the JS framework of the week.

It's ultimately up to the individual dev to decide how deep they want their skills to go.

Today I want to talk about data transfer objects, a software pattern you can use to keep your code better structured and metaphorically coherent.

I’ll define those terms a little better, but first I want to start with a conceptual analogy.

It is a simple truth that, no matter whether you focus on the frontend, the backend or the whole stack, everyone hates CSS.

I kid, but also, I don’t.

CSS is probably among the most reviled of technologies we have to use all the time. The syntax and structure of CSS seems almost intentionally designed to make it difficult to translate from concept to “code,” even simple things. Ask anyone who’s tried to center a div.

And there are all sorts of good historical reasons why CSS is the way it is, but most developers find it extremely frustrating to work with. It’s why we have libraries and frameworks like Tailwind. And Bulma. And Bootstrap. And Material. And all the other tools we use that try their hardest to make sure you never have to write actual while still reaping the benefits of a presentation layer separate from content.

And we welcome these tools, because it means you don’t need to understand the vagaries of CSS in order to get what you want. It’s about developer experience, making it easier on developers to translate their ideas into code.

And in the same way we have tools that cajole CSS into giving us what we want, I want to talk about a pattern that allows you to not worry about anything other than your end goal when you’re building out the internals of your application. It’s a tool that can help you stay in the logical flow of your application, making it easier to puzzle through and communicate about the code you’re writing, both to yourself and others. I’m talking about DTOs.

DTOs

So what is a DTO? Very simply, a data transfer object is a pure, structured data object - that is, an object with properties but no methods. The entire point of the DTO is to make sure that you’re only sending or receiving exactly the data you need to accomplish a given function or task - no more, no less. And you can be assured that your data is exactly the right shape, because it adheres to a specific schema.

And as the “transfer” part of the name implies, a DTO is most useful when you’re transferring data between two points. The title refers to one of the more common exchanges, when you’re sending data between front- and back-end nodes, but there are lots of other scenarios where DTOs come in handy.

Sending just the right amount of data between modules within your application, or consuming data from different sources that use different schemas, are just some of those.

I will note there is literature that suggests the person who coined the term, Martin Fowler, believes that you should not have DTOs except when making remote calls. He’s entitled to his opinion (of which he has many), but I like to reuse concepts where appropriate for consistency and maintainability.

The DTO is one of my go-to patterns, and I regularly implement it for both internal and external use. I’m also aware most people already know what pure data objects are. I’m not pretending we’re inventing the wheel here - the value comes in how they’re applied, systematically.

Advantages

-

For DTOs are a systematic approach to managing how your data flows through and between different parts of your application as well as external data stores.

-

Properly and consistently applied, DTOs can help you maintain what I call metaphorical coherence in your app. This is the idea that the names of objects in your code are the same names exposed on the user-facing side of your application.

Most often, this comes up when we’re discussing domain language - that is, your subject-matter-specific terms (or jargon, as the case may be).

I can’t tell you the number of times I’ve had to actively work out whether a class with the name of “post” refers to a blog entry, or the action of publishing an entry, or a location where someone is stationed. Or whether “class” refers to a template for object creation, a group of children, or one’s social credibility. DTOs can help you keep things organized in your head, and establish a common vernacular between engineering and sales and support and even end-users.

It may not seem like much, but that level of clarity makes talking and reasoning about your application so much easier because you don’t have to jump through mental hoops to understand the specific concept you’re trying to reference.

-

DTOs also help increase type clarity. If you’re at a shop that writes Typescript with “any” as the type for everything, you have my sympathies, and also stop it. DTOs might be the tool you can wield to get your project to start to use proper typing, because you can define exactly what data’s coming into your application, as well as morphing it into whatever shape you need it to be on the other end.

-

Finally, DTOs can help you keep your code as modular as possible by narrowing down the data each section needs to work with. By avoiding tight coupling, we can both minimize side effects and better set up the code for potential reuse.

And, as a bonus mix of points two and four, when you integrated with an external source, DTOs can help you maintain your internal metaphors while still taking advantage of code or data external to your system.

To finish off our quick definition of terms, a reminder that PascalCase is where all the words are jammed together with the first letter of each word capitalized; camelCase is the same except the very first letter is lowercase; and snake case is all lowercase letters joined by underscores.

This is important for our first example.

Use-case 1: FE/BE naming conflicts

The first real-world use-case we’ll look at is what was printed on the box when you bought this talk. That is, when your backend and frontend don’t speak the same language, and have different customs they expect the other to adhere to.

Trying to jam them together is about as effective as when an American has trouble ordering food at a restaurant in Paris and compensates by yelling louder.

In this example, we have a PHP backend talking to a Typescript frontend.

I apologize for those who don’t know one or both languages. For what it’s worth, we’ll try to keep the code as simple as possible to follow, with little-to-no language-specific knowledge required. In good news, DTOs are entirely language agnostic, as we’ll see as we go along.

Backend

class User { public function __construct( public int $id, public string $full_name, public string $email_address, public string $avatar_url ){} }

Per PSR-12, which is the coding standard for PHP, class cases must be in PascalCase, method names must be implemented in camelCase. However, the guide “intentionally avoids any recommendation” as to styling for property names, instead just choosing “consistency.”

Very useful for a style guide!

As you can see, the project we’re working with uses snake case for its property names, to be consistent with its database structure.

Frontend

`class User { userId: number; fullName: string; emailAddress: string; avatarImageUrl: string;

load: (userId: number) => {/* load from DB /}; save: () => {/ persist */}; }`

But Typescript (for the most part, there’s not really an “official” style guide in the same manner but most your Google, your Microsofts, your Facebooks tend to agree) that you should be using camelCase for your variable names.

I realize this may sound nit-picky or like small potatoes to those of used to working as solo devs or on smaller teams, but as organizations scales up consistency and parallelism in your code is vital to making sure both that your code and data have good interoperability, as well as ensuring devs can be moved around without losing significant chunks of time simply to reteach themselves style.

Now, you can just choose one of those naming schemes to be consistent across the frontend and backend, and outright ignore one of the style standards.

Because now your project asking one set of your developers to context-switch specifically for this application. It also makes your code harder to share (unless you adopt this convention-breaking in your extended cinematic code universe). You’ve also probably killed a big rule in your linter, which you now have to customize in all implementations.

OR, we can just use DTOs.

Now, I don’t have a generic preference whether the DTO is implemented on the front- or the back-end — that determination has more to do with your architecture and organizational structure than anything else.

Who owns the contracts in your backend/frontend exchange is probably going to be the biggest determiner - whichever side controls it, the other is probably writing the DTO. Though if you’re consuming an external data source, you’re going to be writing that DTO on the frontend.

Where possible, I prefer to send the cleanest, least amount of data required from my backend, so for our first example we’ll start there. Because we’re writing the DTO in the backend, the data we send needs to conform to the schema the frontend expects - in this instance, Typescript’s camel case.

Backend

class UserDTO { public function __construct( public int $userId, public string $fullName, public string $emailAddress, public string $avatarImageUrl ) {} }

That was easy, right? We just create a data object that uses the naming conventions we’re adopting for sharing data. But of course, we have to get our User model into the DTO. This brings me to the second aspect of DTOs, the secret sauce - the translators.

Translators

function user_to_user_dto(User $user): UserDTO { return new UserDTO( $user->id, $user->full_name, $user->email_address, $user->avatar_url ); }

Very simply, a translator is the function (and it should be no more than one function per level of DTO) that takes your original, nonstandard data and jams it into the DTO format.

Translators get called (and DTOs are created) at points of ingress and egress. Whether that’s internal or external, the point at which a data exchange is made is when a translator is run and a DTO appears – which side of the exchange is up to your implementation. You may also, as the next example shows, just want to include the translator as part of the DTO.

Using a static create method allows us to keep everything nice and contained, with a single call to the class.

`class UserDTO { public function __construct( public int $userId, public string $fullName, public string $emailAddress, public string $avatarImageUrl ) {}

public static function from_user(User $user): UserDTO { return new self( $user->id, $user->full_name, $user->email_address, $user->avatar_url ); } }

$userDto = UserDTO::from_user($user);`

I should note we’re using extremely simplistic base models in these examples. Often, something as essential as the user model is going to have a number of different methods and properties that should never get exposed to the frontend.

While you could do all of this through customizing the serialization method for your object. I would consider that to be a distinction in implementation rather than strategy.

An additional benefit of going the separate DTO route is you now have an explicitly defined model for what the frontend should expect. Now, your FE/BE contract testing can use the definition rather than exposing or digging out the results of your serialization method.

So that’s a basic backend DTO - great for when you control the data that’s being exposed to one or potentially multiple clients, using a different data schema.

Please bear with me - I know this probably seems simplistic, but we’re about to get into the really useful stuff. We gotta lay the groundwork first.

Frontend

Let’s back up and talk about another case - when you don’t control the backend. Now, we need to write the DTO on the frontend.

First we have our original frontend user model.

`class User { userId: number; fullName: string; emailAddress: string; avatarImageUrl: string;

load: (userId: number) => {/* load from DB /}; save: () => {/ persist */}; }`

Here is the data we get from the backend, which I classify as a Response, for organizational purposes. This is to differentiate it from a Payload, which data you send to the API (which we’ll get into those later).

interface UserResponse { id: number; full_name: string; email_address: string; avatar_url: string; }

You’ll note, again, because we don’t control the structure used by the backend, this response uses snake case.

So we need to define our DTO, and then translate from the response.

Translators

You’ll notice the DTO looks basically the same as when we did it on the backend.

interface UserDTO { userId: number; fullName: string; emailAddress: string; avatarImageUrl: string; }

But it's in the translator you can now see some of the extra utility this pattern offers.

const translateUserResponseToUserDTO = (response: UserResponse): UserDTO => ({ userId: response.id, fullName: response.full_name, emailAddress: response.email_address, avatarImageUrl: response.avatar_url });

When we translate the response, we can change the names of the parameters before they ever enter the frontend system. This allows us to maintain our metaphorical coherence within the application, and shield our frontend developers from old/bad/outdated/legacy code on the backend.

Another nice thing about using DTOs in the frontend, regardless of where they come from, is they provide us with a narrow data object we can use to pass to other areas of the application that don’t need to care about the methods of our user object.

DTOs work great in these cases because they allow you to remove the possibility of other modules causing unintended consequences.

Notice that while the User object has load and save methods, our DTO just has the properties. Any modules we pass our data object are literally incapable of propagating manipulations they might make, inadvertently or otherwise. Can’t make a save call if the object doesn’t have a save method.

Use-case 2: Metaphorically incompatible systems

For our second use-case, let’s talk real-world implementation. In this scenario, we want to join up two systems that, metaphorically, do not understand one another.

Magazine publisher

-

Has custom backend system (magazines)

-

Wants to explore new segment (books)

-

Doesn’t want to build a whole new system

I worked with a client, let’s say they’re a magazine publisher. Magazines are a dying art, you understand, so they want to test the waters of publishing books.

But you can’t just build a whole new app and infrastructure for an untested new business model. Their custom backend system was set up to store data for magazines, but they wanted to explore the world of novels. I was asked them build out that Minimum Viable Product.

Existing structure

`interface Author { name: string; bio: string; }

interface Article { title: string; author: Author; content: string; }

interface MagazineIssue { title: string; issueNo: number; month: number; year: number; articles: Article[]; }`

This is the structure of the data expected by both the existing front- and back-ends. Because everything’s one word, we don’t even need to worry about incompatible casing.

Naive implementation This new product requires performing a complete overhaul of the metaphor.

`interface Author { name: string; bio: string; }

interface Chapter { title: string; author: Author; content: string; }

interface Book { title: string; issueNo: number; month: number; year: number; articles: Chapter[]; }`

But we are necessarily limited by the backend structure as to how we can persist data.

If we just try to use the existing system as-is, but change the name of the interfaces, it’s going to present a huge mental overhead challenge for everyone in the product stack.

As a developer, you have to remember how all of these structures map together. Each chapter needs to have an author, because that’s the only place we have to store that data. Every book needs to have a month, and a number. But no authors - only chapters have authors.

So we could just use the data structures of the backend and remember what everything maps to. But that’s just asking for trouble down the road, especially when it comes time to onboard new developers. Now, instead of them just learning the system they’re working on, they essentially have to learn the old system as well.

Plus, if (as is certainly the goal) the transition is successful, now their frontend is written in the wrong metaphor, because it’s the wrong domain entirely. When the new backend gets written, we’re going to have to the exact same problem in the opposite direction.

I do want to take a moment to address what is probably obvious – yes, the correct decision would be to build out a small backend that can handle this, but I trust you’ll all believe me when I say that sometimes decisions get made for reasons other than “what makes the most sense for the application’s health or development team’s morale.”

And while you might think that find-and-replace (or IDE-assisted refactoring) will allow you to skirt this issue, please trust me that you’re going to catch 80-90% of cases and spend twice as much time fixing the rest as it would have to write the DTOs in the first place.

Plus, as in this case, your hierarchies don’t always match up properly.

What we ended up building was a DTO-based structure that allowed us to keep metaphorical coherence with books but still use the magazine schema.

Proper implementation

You’ll notice that while our DTO uses the same basic structures (Author, Parts of Work [chapter or article], Work as a Whole [book or magazine]), our hierarchies diverge. Whereas Books have one author, Magazines have none; only Articles do.

The author object is identical from response to DTO.

You’ll also notice we completely ignore properties we don’t care about in our system, like IssueNo.

How do we do this? Translators!

Translating the response

We pass the MagazineResponse in to the BookDTO translator, which then calls the Chapter and Author DTO translators as necessary.

`export const translateMagazineResponseToAnthologyBookDTO = (response: MagazineResponse): AnthologyBookDTO => { const chapters = (response.articles.length > 0) ? response.articles.forEach((article) => translateArticleResponseToChapterDTO(article)) : []; const authors = [ ...new Set( chapters .filter((chapter) => chapter.author) .map((chapter) => chapter.author) ) ]; return {title: response.title, chapters, authors}; };

export const translateArticleResponseToChapterDTO = (response: ArticleResponse): ChapterDTO => ({ title: response.title, content: response.content, author: response.author });`

This is also the first time we’re using one of the really neat features of translators, which is the application of logic. Our first use is really basic, just checking if the Articles response is empty so we don’t try to run our translator against null. This is especially useful if your backend has optional properties, as using logic will be necessary to properly model your data.

But logic can also be used to (wait for it) transform your data when we need to.

Remember, in the magazine metaphor, articles have authors but magazine issues don’t. So when we’re storing book data, we’re going to use their schema by grabbing the author of the first article, if it exists, and assign it as the book’s author. Then, our chapters ignore the author entirely, because it’s not relevant in our domain of fiction books with a single author.

Because the author response is the same as the DTO, we don’t need a translation function. But we do have proper typing so that if either of them changes in the future, it should throw an error and we’ll know we have to go back and add a translation function.

The payload

Of course, this doesn’t do us any good unless we can persist the data to our backend. That’s where our payload translators come in - think of Payloads as DTOs for the anything external to the application.

`interface AuthorPayload name: string; bio: string; }

interface ArticlePayload { title: string; author: Author; content: string; }

interface MagazineIssuePayload { title: string; issueNo: number; month: number; year: number; articles: ArticlePayload[]; }`

For simplicity’s sake we’ll assume our payload structure is the same as our response structure. In the real world, you’d likely have some differences, but even if you don’t it’s important to keep them as separate types. No one wants to prematurely optimize, but keeping the response and payload types separate means a change to one of them will throw a type error if they’re no longer parallel, which you might not notice with a single type.

Translating the payload

`export const translateBookDTOToMagazinePayload = (book: BookDTO): MagazinePayload => ({ title: book.title, articles: (book.chapters.length > 0) ? book.chapters.forEach((chapter) => translateChapterDTOToArticlePayload(chapter, book) : [], issueNo: 0, month: 0, year: 0, });

export const translateChapterDTOToArticlePayload = (chapter: ChapterDTO, book: BookDTO): ArticlePayload => ({ title: chapter.title, author: book.author, content: chapter.content });`

Our translators can be flexible (because we’re the ones writing them), allowing us to pass objects up and down the stack as needed in order to supply the proper data.

Note that we’re just applying the author to every article, because a) there’s no harm in doing so, and b) the system like expects there be an author associated with every article, so we provide one. When we pull it into the frontend, though, we only care about the first article.

We also make sure to fill out the rest of the data structure we don’t care about so the backend accepts our request. There may be actual checks on those numbers, so we might have to use more realistic data, but since we don’t use it in our process, it’s just a question of specific implementation.

So, through the application of ingress and egress translators, we can successfully keep our metaphorical coherence on our frontend while persisting data properly to a backend not configured to the task. All while maintaining type safety. That’s pretty cool.

The single biggest thing I want to impart from this is the flexibility that DTOs offer us.

Use-case 3: Using the smallest amount of data required

When working with legacy systems, I often run into a mismatch of what the frontend expects and what the backend provides; typically, this results in the frontend being flooded an overabundance of data.

These huge data objects wind up getting passed around and used on the frontend because, for example, that’s what represents the user, even if you only need a few properties for any given use-case.

Or, conversely, we have the tiny amount of data we want to change, but the interface is set up expecting the entirety of the gigantic user object. So we wind up creating a big blob of nonsense data, complete with a bunch of null properties and only the specific ones we need filled in. It’s cumbersome and, worse, has to be maintained so that whenever any changes to the user model need to be propagated to your garbage ball, even if those changes don’t touch the data points you care about.

One way to eliminate the data blob is to use DTOs to narrowly define which data points a component or class needs in order to function. This is what I call minimizing touchpoints, referring to places in the codebase that need to be modified when the data structure changes.

One way to eliminate the data blob is to use DTOs to narrowly define which data points a component or class needs in order to function. This is what I call minimizing touchpoints, referring to places in the codebase that need to be modified when the data structure changes.

In this scenario, we’re building a basic app and we want to display an avatar for a user. We need their name, a picture and a color for their frame.

const george = { id: 303; username: 'georgehernandez'; groups: ['users', 'editor'], sites: ['https://site1.com'], imageLocation: '/assets/uploads/users/gh-133133.jpg'; profile: { firstName: 'George'; lastName: 'Hernandez'; address1: '738 Evergreen Terrace'; address2: ''; city: 'Springfield'; state: 'AX'; country: 'USA'; favoriteColor: '#1a325e'; } }

What we have is their user object, which contains a profile and groups and sites the user is assigned to, in addition to their address and other various info.

Quite obviously, this is a lot more data than we really need - all we care about are three data points.

`class Avatar { private imageUrl: string; private hexColor: string; private name: string;

constructor(user: User) { this.hexColor = user.profile.favoriteColor: this.name = user.profile.firstName

- ' '

- user.profile.lastName;

this.imageUrl = user.imageLocation;

}

}`

This Avatar class works, technically speaking, but if I’m creating a fake user (say it’s a dating app and we need to make it look like more people are using than actually is the case), I now have to create a bunch of noise to accomplish my goal.

const lucy = { id: 0; username: ''; groups: []; sites: []; profile: { firstName: 'Lucy'; lastName: 'Evans'; address1: ''; address2: ''; city: ''; state: ''; country: ''; } favoriteColor: '#027D01' }

Even if I’m calling from a completely separate database and class, in order to instantiate an avatar I still need to provide the stubs for the User class.

Or we can use DTOs.

`class Avatar { private imageUrl: string; private hexColor: string; private name: string;

constructor(dto: AvatarDTO) { this.hexColor = dto.hexColor: this.name = dto.name; this.imageUrl = dto.imageUrl; } }

interface AvatarDTO { imageUrl: string; hexColor: string; name: string; }

const translateUserToAvatarDTO = (user: User): AvatarDTO => ({ name: [user.profile.firstName, user.profile.lastName].join(' '), imageUrl: user.imageLocation, hexColor: user.profile.favoriteColor });`

By now, the code should look pretty familiar to you. This pattern is really not that difficult once you start to use it - and, I’ll wager, a lot of you are already using it, just not overtly or systematically. The bonus to doing it in a thorough fashion is that refactoring becomes much easier - if the frontend or the backend changes, we have a single point from where the changes emanate, making them much easier to keep track of.

Flexibility

But there’s also flexibility. I got some pushback from implementing the AvatarDTO; after all, there were a bunch of cases already extant where people were passing the user profile, and they didn’t want to go find them. As much as I love clean data, I am a consultant; to assuage them, I modified the code so as to not require extra work (at least, at this juncture).

`class Avatar { private avatarData: AvatarDTO;

constructor(user: User|null, dto?: AvatarDTO) { if (user) { this.avatarData = translateUserToAvatarDTO(user); } else if (dto) { this.avatarData = dto; } } }

new Avatar(george); new Avatar(null, { name: 'Lucy Evans', imageUrl: '/assets/uploads/users/le-319391.jpg', hexColor: '#fc0006' });`

Instead of requiring the AvatarDTO, we still accept the user as the default argument, but you can also pass it null. That way I can pass my avatar DTO where I want to use it, but we take care of the conversion for them where the existing user data is passed in.

Use-case 4: Security

The last use-case I want to talk about is security. I assume some to most of you already get where I’m going with this, but DTOs can provide you with a rock-solid way to ensure you’re only sending data you’re intending to.

Somewhat in the news this month is the Spoutible API breach; if you’ve never heard of it, I’m not surprised. Spoutible a Twitter competitor, notable mostly for its appalling approach to API security.

I do encourage all of you to look this article up on troyhunt.com, as the specifics of what they were exposing are literally unbelievable.

{ err_code: 0, status: 200, user: { id: 23333, username: "badwebsite", fname: "Brad", lname: "Website", about: "The collector of bad website security data", email: 'fake@account.com', ip_address: '0.0.0.0', verified_phone: '333-331-1233', gender: 'X', password: '$2y$10$r1/t9ckASGIXtRDeHPrH/e5bz5YIFabGAVpWYwIYDCsbmpxDZudYG' } }

But for the sake of not spoiling all the good parts, I’ll just show you the first horrifying section of data. For authenticated users, the API appeared to be returning the entire user model - mundane stuff like id, username, a short user description, but also the password hash, verified phone number and gender.

Now, I hope it goes without saying that you should never be sending anything related to user passwords, whether plaintext or hash, from the server to the client. It’s very apparent when Spoutible was building its API that they didn’t consider what data was being returned for requests, merely that the data needed to do whatever task was required. So they were just returning the whole model.

If only they’d used DTOs! I’m not going to dig into the nitty-gritty of what it should have looked like, but I think you can imagine a much more secure response that could have been sent back to the client.

Summing up

If you get in the practice of building DTOs, it’s much easier to keep control of precisely what data is being sent. DTOs not only help keep things uniform and unsurprising on the frontend, they can also help you avoid nasty backend surprises as well.

To sum up our little chat today: DTOs are a great pattern to make sure you’re maintaining structured data as it passes between endpoints.

Different components only have to worry about exactly the data they need, which helps both decrease unintended consequences and decrease the amount of touchpoints in your code you need to deal with when your data structure changes. This, in turn, will help you maintain modular independence for your own code.

It also allows you to confidently write your frontend code in a metaphorically coherent fashion, making it easier to communicate and reason about.

And, you only need to conform your data structure to the backend’s requirements at the points of ingress and egress - Leaving you free to only concern your frontend code with your frontend requirements. You don’t have to be limited by the rigid confines backend’s data schema.

Finally, the regular use of DTOs can help put you in the mindset of vigilance in regard to what data you’re passing between services, without needing to worry that you’re exposing sensitive data due to the careless conjoining of model to API controller.

🎵 I got a DTOooooo

“[Random AI] defines ...” has already started to replace “Webster’s defines ...” as the worst lede for stories and presentations.

I let the AI interview in the playbill slide because the play was about AI, but otherwise, no bueno.

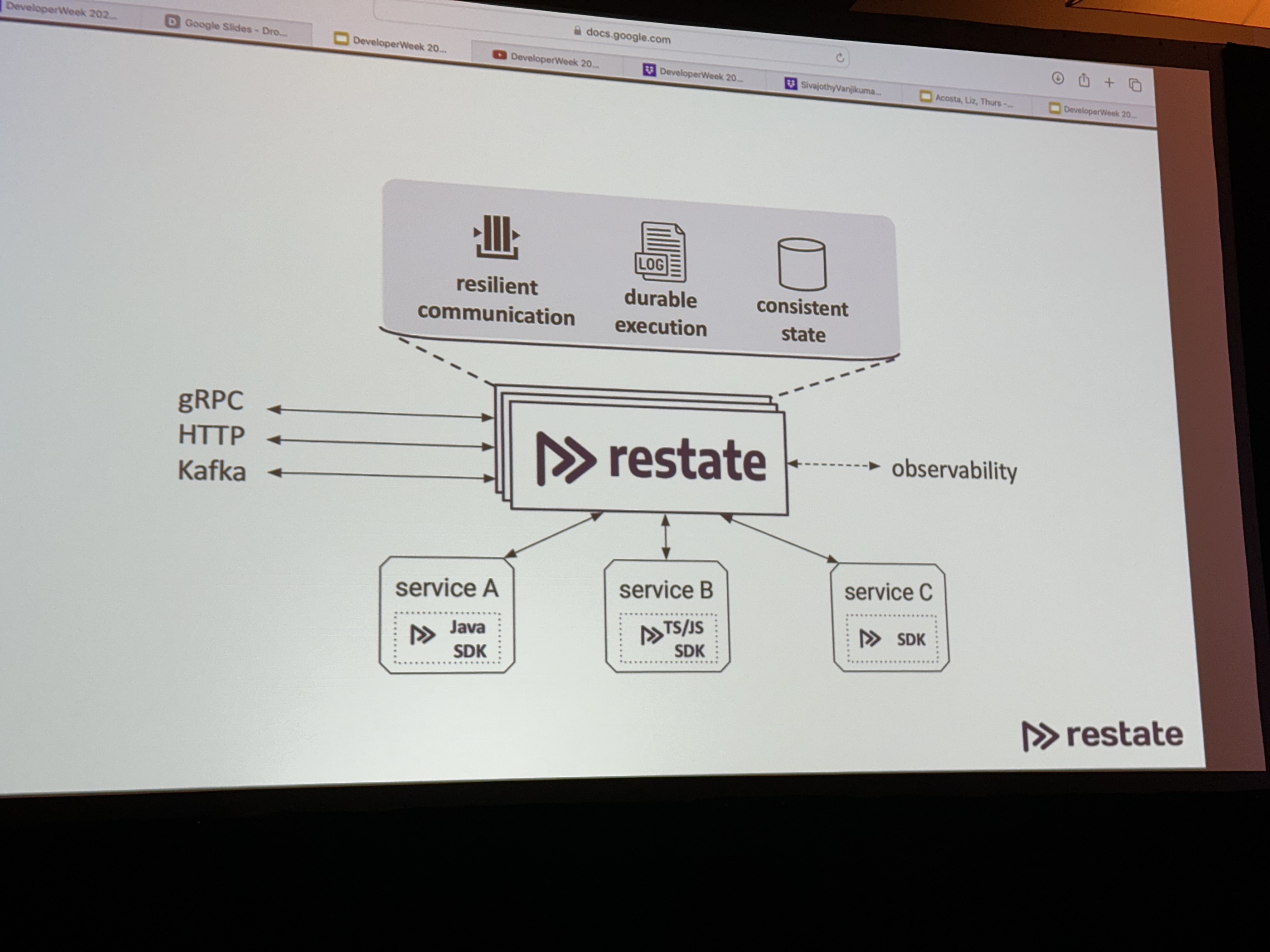

The way to guarantee durability and failure recovery in serverless orchestration and coordination is … a server and database in the middle of your microservices.

I’m sure it’s a great product, but come on.

The way to guarantee durability and failure recovery in serverless orchestration and coordination is … a server and database in the middle of your microservices.

I’m sure it’s a great product, but come on.

I have previously mentioned that I love NextDNS, but they do not make certain fundamental things, like managing your block and allow lists, very easy. Quite often I'll hit a URL that's blocked that I'd like to see - rather than use their app, I have to load their (completely desktop-oriented) website, navigate to the right tab, then add the URL in.

That's annoying.

Without writing an iOS app all of its own (which sounds like a lot of work), I wanted an easy to way to push URLs to the block or deny list. So I wrote an iOS Shortcut that works with a PHP script to send the appropriate messages.

You can find the shortcut here.

The PHP script can found at this Gist. You'll need to set the token, API key (API key can be found at the bottom of your NextDNS profile) and profile ID variables in the script. The token is what you'll use to secure your requests from your phone to the server.

I thought about offering a generic PHP server that required you to set everything in Shortcuts, but that's inherently insecure for everyone using it, so I decided against it. I think it would be possible to do this all in Shortcuts, but Shortcuts drives me nuts for anything remotely complex, and this does what I need it to.

It really is annoying how hard it is to manage a basic function. NextDNS also doesn't seem to have set their CORS headers properly for OPTIONS requests, which are required for browser-based interactions because of how they dictated the API token has to be sent.

At least I finished it, eventually!

As part of my plan to spend more time bikeshedding building out my web presence than actually creating content, I wanted to build an iOS app that allowed me to share short snippets of text or photos to my blog. I've also always wanted to understand Swift generally and building an iOS app specifically, so it seemed like a nice little rabbit hole.

With the help of Swift UI Apprentice, getting a basic app that posted a content, headline and tags to my API wasn't super difficult (at least, it works in the simulator. I'm not putting it on my phone until it's more useful). I figured adding a share extension would be just as simple, with the real difficulty coming when it came time to posting the image to the server.

Boy was I wrong.

Apple's documentation on Share Extensions (as I think they're called? But honestly it's hard to tell) is laughably bad, almost entirely referring to sharing things out from your app, and even the correct shitty docs haven't been updated in it looks like 4+ years.

There are some useful posts out there, but most/all of them assume you're using UIKit. Since I don't trust Apple not to deprecate a framework they've clearly been dying to phase out for years, I wanted to stick to SwiftUI as much as I could. Plus, I don't reallllly want to learn two paradigms to do the same thing. I have enough different references to keep in my head switching between languages.

Thank god for Oluwadamisi Pikuda, writing on Medium. His post is an excellent place to get a good grasp on the subject, and I highly suggest visiting it if you're stuck. However, since Medium is a semi-paywalled content garden, I'm going to provide a cleanroom implementation here in case you cannot access it.

It's important to note that the extension you're creating is, from a storage and code perspective, a separate app. To the point that technically I think you could just publish a Share Extension, though I doubt Apple would allow it. That means if you want to share storage between your extension and your primary app, you'll need to create an App Group to share containers. If you want to share code, you'll need to create an embedded framework.

But once you have all that set up, you need to actually write the extension. Note that for this example we're only going to be dealing with text shared from another app, with a UI so you can modify it. You'll see where you can make modifications to work with other types.

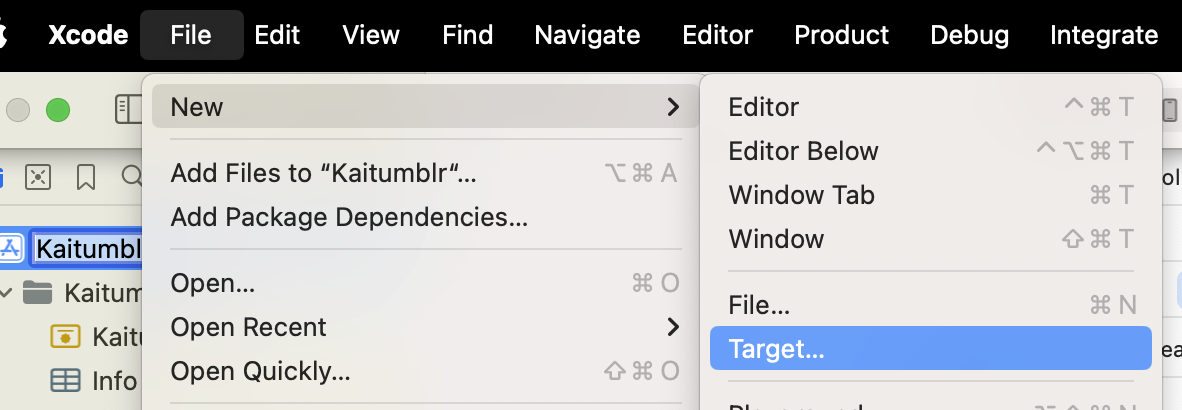

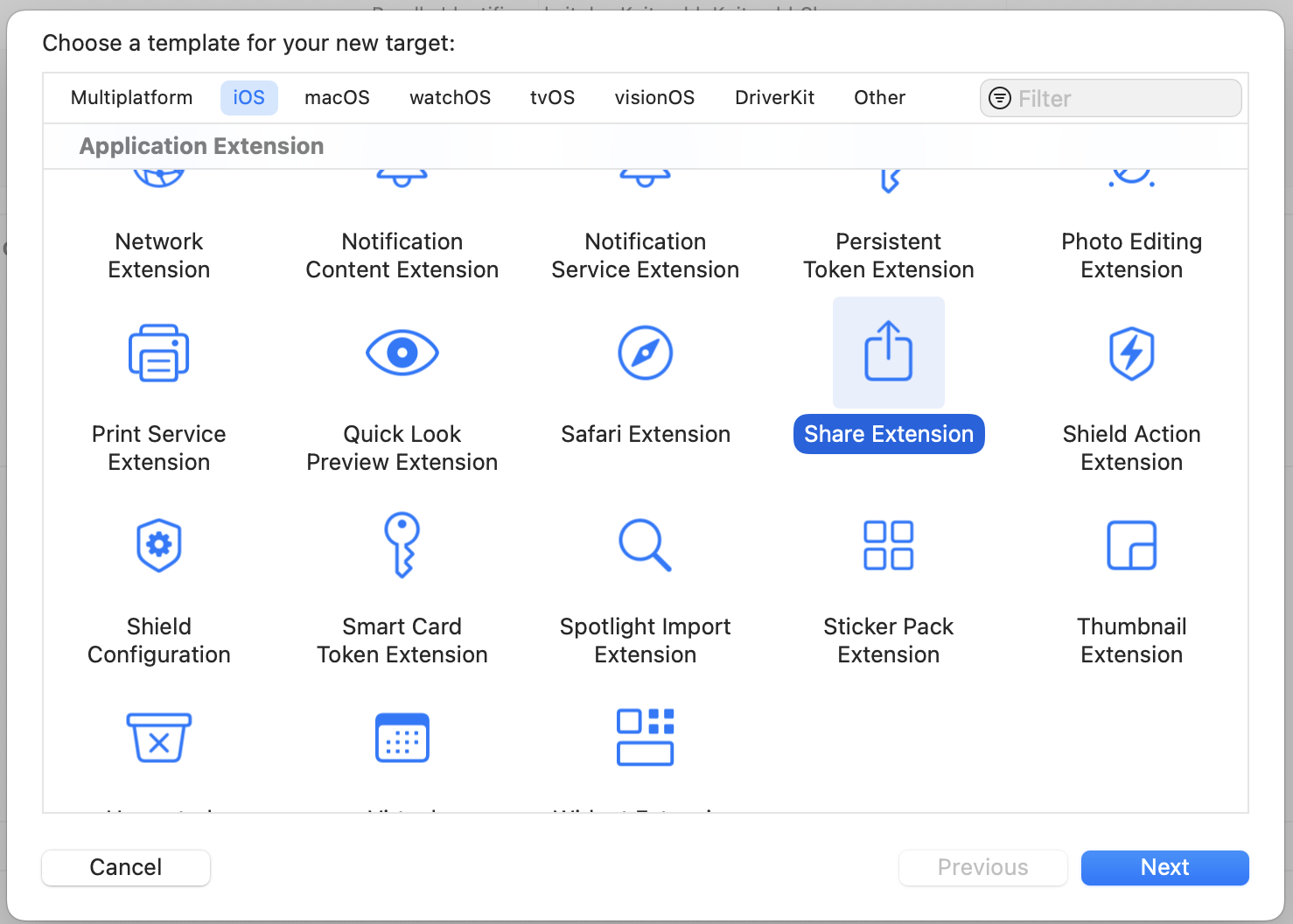

You start by creating a new target (File -> New -> Target, then in the modal "Share Extension").

Once you fill out the info, this will create a new directory with a UIKit Storyboard file (MainInterface), ViewController and plist. We're not gonna use hardly any of this. Delete the Storyboard file. Then change your ViewController to use the

Once you fill out the info, this will create a new directory with a UIKit Storyboard file (MainInterface), ViewController and plist. We're not gonna use hardly any of this. Delete the Storyboard file. Then change your ViewController to use the UIViewController class. This is where we'll define what the user sees when content is shared. The plist is where we define what can be passed to our share extension.

There are only two functions we're concerned about in the ViewController — viewDidLoad() and close(). Close is going to be what closes the extension while viewDidLoad, which inits our code when the view is loaded into memory.

For close(), we just find the extensionContext and complete the request, which removes the view from memory.

viewDidLoad(), however, has to do more work. We call the super class function first, then we need to make sure we have access to the items that are been shared to us.

`import SwiftUI

class ShareViewController: UIViewController {

override func viewDidLoad() { super.viewDidLoad()

// Ensure access to extensionItem and itemProvider guard let extensionItem = extensionContext?.inputItems.first as? NSExtensionItem, let itemProvider = extensionItem.attachments?.first else { self.close() return } }

func close() {

self.extensionContext?.completeRequest(returningItems: [], completionHandler: nil)

}

}</pre><p>Since again we're only working with text in this case, we need to verify the items are the correct type (in this case, UTType.plaintext`).

`import UniformTypeIdentifiers import SwiftUI

class ShareViewController: UIViewController { override func viewDidLoad() { ...

let textDataType = UTType.plainText.identifier

if itemProvider.hasItemConformingToTypeIdentifier(textDataType) {

// Load the item from itemProvider

itemProvider.loadItem(forTypeIdentifier: textDataType , options: nil) { (providedText, error) in

if error != nil {

self.close()

return

}

if let text = providedText as? String {

// this is where we load our view

} else {

self.close()

return

}

}

}</pre><p>Next, let's define our view! Create a new file, ShareViewExtension.swift. We are just editing text in here, so it's pretty darn simple. We just need to make sure we add a close()function that callsNotificationCenter` so we can close our extension from the controller.

`import SwiftUI

struct ShareExtensionView: View { @State private var text: String

init(text: String) { self.text = text }

var body: some View { NavigationStack{ VStack(spacing: 20){ Text("Text") TextField("Text", text: $text, axis: .vertical) .lineLimit(3...6) .textFieldStyle(.roundedBorder)

Button { // TODO: Something with the text self.close() } label: { Text("Post") .frame(maxWidth: .infinity) } .buttonStyle(.borderedProminent)

Spacer() } .padding() .navigationTitle("Share Extension") .toolbar { Button("Cancel") { self.close() } } } }

// so we can close the whole extension func close() { NotificationCenter.default.post(name: NSNotification.Name("close"), object: nil) } }`

Back in our view controller, we import our SwiftUI view.

`import UniformTypeIdentifiers import SwiftUI

class ShareViewController: UIViewController { override func viewDidLoad() { ... if let text = providedText as? String { DispatchQueue.main.async { // host the SwiftUI view let contentView = UIHostingController(rootView: ShareExtensionView(text: text)) self.addChild(contentView) self.view.addSubview(contentView.view)

// set up constraints contentView.view.translatesAutoresizingMaskIntoConstraints = false contentView.view.topAnchor.constraint(equalTo: self.view.topAnchor).isActive = true contentView.view.bottomAnchor.constraint (equalTo: self.view.bottomAnchor).isActive = true contentView.view.leftAnchor.constraint(equalTo: self.view.leftAnchor).isActive = true contentView.view.rightAnchor.constraint (equalTo: self.view.rightAnchor).isActive = true } } else { self.close() return } } }`

In that same function, we'll also add an observer to listen for that close event, and call our close function.

NotificationCenter.default.addObserver(forName: NSNotification.Name("close"), object: nil, queue: nil) { _ in DispatchQueue.main.async { self.close() } }

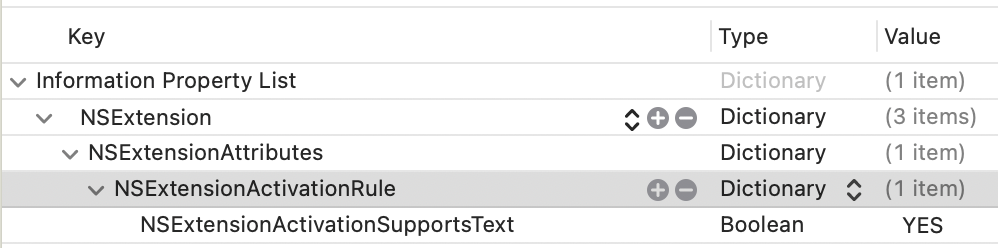

The last thing you need to do is register that your extension can handle Text. In your info.plist, you'll want to add an NSExtensionAttributes dictionary with an NSExtensionActivtionSupportsText boolean set to true.

You should be able to use this code as a foundation to accept different inputs and do different things. It's a jumping-off point! Hope it helps.

You should be able to use this code as a foundation to accept different inputs and do different things. It's a jumping-off point! Hope it helps.

I later expanded the app's remit to include cross-posting to BlueSky and Mastodon, which is a double-bonus because BlueSky STILL doesn't support sharing an image from another application (possibly because they couldn't find the Medium post???)

I've recently been beefing up my homelab game, and I was having issues getting a Gotify secure websocket to connect. I love the Caddy webserver for both prod and local installs because of how easy it easy to configure.

For local installs, it defaults to running its own CA and issuing a certificate. Now, if you're only running one instance of Caddy on the same machine you're accessing, getting the certs to work in browsers is easy as running caddy trust.

But in a proper homelab scenario, you're running multiple machines (and, often, virtualized machines within those boxes), and the prospect of grabbing the root cert for each just seemed like a lot of work. At first, I tried to set up a CA with Smallstep, but was having enough trouble just getting all the various pieces figured out that figured there had to be an easier way.

There was.

I registered a domain name (penginlab.com) for $10. I set it up with an A record pointing at my regular dev server, and then in the Caddyfile gave it instructions to serve up the primary domain, and a separate instance for a wildcard domain.

When LetsEncrypt issues a wildcard domain, it uses a DNS challenge, meaning it only needs a TXT record inserted into your DNS zone to prove it should issue you the server. Assuming your registrar is among those included in the Caddy DNS plugins, you can set your server to handle that automatically.

(If your registrar is not on that list, you can always use

certbot certonly --manual

and enter the TXT record yourself. You only need to do it once a quarter.)

Now we have a certificate to use to validly sign HTTPS connections for any subdomain for penginlab.com. You simply copy down the fullchain.pem and privkey.pem files to your various machines (I set up a bash script that scps the file down to one of my local machines and then scps it out to everywhere it needs to go on the local network.)

Once you have the cert, you can set up your caddy servers to use it using the tls directive:

tls /path/to/fullchain.pem /path/to/privkey.pem

You'll also need to update your local DNS (since your DNS provider won't let you point public URLs at private IP addresses), but I assume you were doing that anyway (I personally use NextDNS for a combination of cloud-based ad-blocking and lab DNS management).

Bam! Fully accepted HTTPS connections from any machine on your network. And all you have to do is run one bash script once a quarter (which you can even throw on a cron). Would that all projects have so satisfying and simple a solution.

I'm definitely not brave enough to put it on a cron until I've run it manually at least three times, TBH. But it's a nice thought!

Re: Apple’s convoluted EU policies

It's surprising how often D&D is relevant in my everyday life. Most people who play D&D are in it to have fun. They follow the rule - not just the letter of the law, but the spirit.

But every once in a while you'll encounter a "rules lawyer," a player who's more concerned with making sure you observe and obey every tiny rule, punish every pecadillo, than actually having fun.

All the worse when it's your GM, the person in charge of running the game.

But there's one thing you learn quickly - if someone is trying to game the rules, the only way to win (or have any fun) is play the game right back.

For smaller/mid-tier devs, if you're only offering free apps you should probably just continue in the App Store.

But for larger devs who might run afoul of the new guidelines where apps distributed outside the App Store get charged a fee every time they go over a million users?

Oops, Apple just created collectible apps, where if you have Facebook (and not Facebook2), we know you got in early. Think about it: Same codebase, different appId. The external app stores can even set up mechanisms for this to work - every time you hit 999,000 installs, it creates a new listing that just waits for you to upload the new binary (and switches when you hit 995K). Now your users are incentivized to download your app early, in case becomes the big thing. Lower app # is the new low user ID.

If I'm Microsoft, I'm putting a stunted version of my app in the App Store (maybe an Office Documents Viewer?) for free, with links telling them if they want to edit they have go to the Microsoft App Store to download the app where Apple doesn't get a dime (especially if Microsoft uses the above trick to roll over the app every 995K users).

Even in the world where (as I think is the case in this one) Apple says all your apps have to be on the same licensing terms (so you can't have some App Store and some off-App Store), it costs barely anything to create a new LLC (and certainly less than the 500K it would cost if your app hits a million users). Apple's an Irish company, remember? So one of your LLCs is App Store, and the other is external.

To be clear, I don't like this setup. I think the iPhone should just allow sideloading, period. Is all of this more complicated for developers? Absolutely! Is the minimal amount of hassle worth saving at least 30% percent of your current revenue (or minimum $500K if you go off-App Store)? For dev shops of a certain size, I would certainly think so.

The only way to have fun with a rules lawyer is to get them to relax, or get them to leave the group. You have to band together to make them see the error of their ways, or convince them it's so much trouble it's not worth bothering to argue anymore.

Yes, Apple is going to (rules-)lawyer this, but they made it so convoluted I would be surprised if they didn't leave some giant loopholes, and attempting to close them is going to bring the EU down on them hard. If the EU is even going to allow this in the first place.

I'll be hitting the lecture circuit again this year, with three conferences planned for the first of 2024.

In February, I'll be at Developer Week in Oakland (and online!), talking about Data Transfer Objects.

In March, I'll be in Michigan for the Michigan Technology Conference, speaking about clean code as well as measuring and managing productivity for dev teams.

And in April I'll be in Chicago at php[tek] to talk about laws/regulations for developers and DTOs (again).

Hope to see you there!

Who holds a conference in the upper Midwest in March???

Hey everybody, in case you wanted to see my face in person, I will be speaking at LonghornPHP, which is in Austin from Nov. 2-4. I've got two three things to say there! That's twice thrice as many things as one thing! (I added a last-minute accessibility update).

In case you missed it, I said stuff earlier this year at SparkConf in Chicago!

I said stuff about regulations (HIPAA, FERPA, GDPR, all the good ones) at the beginning of this year. This one is available online, because it was only ever available online:

I am sorry for talking so fast in that one, I definitely tried to cover more than I should have. Oops!

The SparkConf talks are unfortunately not online yet (for reasons), and I'm doubtful they ever will be.

Block themes parsing shortcodes in user generated data; thanks to Liam Gladdy of WP Engine for reporting this issue

As a reminder, from Semver.org:

Given a version number MAJOR.MINOR.PATCH, increment the: 1. MAJOR version when you make incompatible API changes 2. MINOR version when you add functionality in a backward compatible manner 3. PATCH version when you make backward compatible bug fixes

As it turns out, just because you label it as a "security" patch doesn't make it OK to completely annihilate functionality that numerous themes depend on.

This bit us on a number of legacy sites that depend entirely on shortcode parsing for functionality. Because it's a basic feature. We sanitize ACTUAL user-generated content, but the CMS considers all database content to be "user content."

WordPress is not stable, should not be considered to be an enterprise-caliber CMS, and should only be run on WordPress.com using WordPress.com approved themes. Dictator for life Matt Mullenweg has pretty explicitly stated he considers WordPress' competitors to be SquareSpace and Wix. Listen to him.

Friends don't let their friends use WordPress

Note: This site now runs on Statamic

I knew I needed a new website. My go-to content management system was no longer an option, and I investigated some of the most popular alternatives. The first thing to do, as with any project, was ascertain the requirements. My biggest concerns were a) ability to create posts and pages, b) image management, and c) easy to use as a writer and a developer (using my definition of easy to use, since it was my site).

I strongly considered using Drupal, since that's what we (were, until a month ago) going to use at work, but it seemed like a lot of work and overhead to get the system to do what I wanted it to. I (briefly) looked at Joomla, but it too seemed bloated with a fairly unappealing UI/UX on the backend. I was hopeful about some of the Laravel CMSes, but they too seemed to have a bloated foundation for my needs.

I also really dug into the idea of flat-file CMSes, since most (all) of my content is static, but I legitimately couldn't find one that didn't require a NodeJS server. I don't mind Node when it's needed, but I already have a scripting language (PHP) that I was using, and didn't feel like going through the hassle of getting a Node instance going as well.

(Later on I found KirbyCMS, which is probably what I'm going to try for my next client or work project, but I both found it too late in the process and frankly didn't want to lose out on the satisfaction of getting it running when I was ~80% of the way done.)

As I was evaluating the options, in addition to the dealbreakers, I kept finding small annoyances. The backend interface was confusing, or required too many clicks to get from place to place; the speed to first paint was insane; just the time waiting for the content editor to load after I clicked it seemed interminable. At the same time, I was also going through a similarly frustrating experience with cloud music managers, each with a vital missing feature or that implemented a feature in a wonky way.

Then I had an epiphany: Why not just build my own?

I know, I know. It's a tired developer cliche that anything Not Built Here is Wrong. But as I thought it over more, the concept intrigued me. I wasn't setting out to replace WordPress or Drupal or one of the heavy-hitters; I just wanted a base to build from that would allow me to create posts, pages, and maybe some custom ideas later down the road (links with commentary; books from various sources, with reviews/ratings). I would be able to keep it slim, as I didn't have to design for hundreds of use cases. Plus, it would be an excellent learning opportunity, that would allow me to delve deeply into how other systems work and how I might improve upon them (for my specific use case; I make no claim I can do it better than anyone else).

Besides, how long could it take?

Four months later, LinkCMS is powering this website. It's fast and light, it can handle image uploads, it can create pages and posts ... mostly. Hey, it fulfills all the requirements!

Don't get me wrong, it's still VERY MUCH a beta product. I am deep in the dogfooding process right now (especially with some of the text editing, which I'll get into below), but I cannot describe the satisfaction of being able to type in the URL and see the front end, or log in to the backend and make changes, and know that I built it from the ground-up.

LinkCMS is named after its mascot (and, she claims, lead developer), Admiral Link Pengin, who is the best web developer (and admiral) on our Technical Penguins team.

I don't want to go through the whole process in excruciating detail, both because that'd be boring and because I don't remember everything with that many details anyway. I do, however, want to hit the highlights.

-

Flight is a fantastic PHP routing framework. I've used it for small projects in the past, and it was pretty much a no-brainer when I decided I wanted to keep things light and simple. It can get as complicated as you want, but if you browse through the codebase you'll see that it's fairly basic, both for ease of understand and because it was easier to delete and edit routes as separate items.

-

LinkCMS uses the Twig templating system, mostly because I like the syntax.

-

The above two dependencies are a good example of a core principle I tried to keep to: Only use libraries I actually need, and don't use a larger library when a smaller one will do. I could have thrown together a whole CMS in Laravel pretty quickly, or used React or Vue for the front end, but it would have come at the expense of stability and speed, as well as (for the latter two) a laborious build process.

-

I don't hate everything about WordPress! I think block-based editing is a great idea, so this site is built on (custom) blocks. My aim is to have the content be self-contained in a single database row, built around actual HTML if you want to pull it out.

-

One of my favorite features is a Draft Content model. With most CMSes, once a page is published, if you make any changes and save them, those changes are immediately displayed on the published page. At best, you can make the whole post not published and check it without displaying the changes to the public. LinkCMS natively holds two copies of the content for all posts and pages - Draft and Published. If you publish a page, then make edits and save it, those changes are saved to the Draft content without touching the Published part. Logged-in users can preview the Draft content as it will look on the page. Once it's ready, you can Publish the page (these are separate buttons, as seen in the screenshots) for public consumption. Think of it as an integrated staging environment. On the roadmap is a "revert" function so you can go back to the published version if you muck things up too much.

-

One of the things that was super important to me was that everything meet WCAG AA accessibility. Making this a goal significantly limited my options when it came to text editors. There are a few out there that are accessible, but they are a) huge (like, nearly half a megabyte of more, gzipped) and b) much more difficult to extend in the ways I wanted to. Again, with a combination of optimism (I can learn a lot by doing this!) and chutzpah (this is possible!), I decided to write my own editor, Hat (named after Link's penguin, Hat, who wears the same hat as the logo). I'm really pleased with how the Hat editor turned out, though it does still have some issues I discovered while building this site that are in desperate need of fixing (including if you select text and bold it, then immediately try to un-bold it, it just bolds the whole paragraph). But I'm extremely proud to say it that both HatJS and LinkCMS are 100% WCAG AA 2.1 accessible, to the best of my knowledge.

-

Since I was spending so much time on it, I wanted to make sure I could use LinkCMS for future projects while still maintaining the ability to update the core without a lot of complicated git-ing or submodules. I structured the project so that core functionality lives in the primary repo, and everything else (including pages and posts) live in self-contained Modules (let's be real, they're plugins, but it's my playground, so I get to name the imaginary territory). This means you can both update core and modules, AND you only need to have those components included that you're actually using.

-

I used a modified Model-View-Controller architecture: I call the pieces Models, Controllers and Actors. Models and Controllers do what you'd expect. Actors are what actually make changes and make things work. It's easier for me to conceptualize each piece rather than using "View" as the name, which to my mind leaves a lot of things out. I'm aware of the MVAC approach, and I suppose technically the templates are the View, but I lumped the routes and templating in under Actors (Route and Display, accordingly), and it works for me.

I don't think LinkCMS is in a state where someone else could install it right now. (For starters, I'm fairly certain I haven't included the basic SQL yet.) The code is out there and available, and hopefully soon I can get it to a presentable state.

But the end goal of all this was, again, not to be a CMS maven challenging the incumbents. I wanted to learn more about how these systems work (the amount of insight I gained into Laravel through building my own is astounding, to me), and craft a tool that allows me to build small sites and projects, on my own terms, with minimal dependencies and maximum stability.

Mission accomplished.

I set out to build my own CMS in an attempt to circumvent some of the problems I'd had with others in the past. I wound up inventing a whole new set of problems! What a neat idea.

Email newsletters are the future. And the present. And also, at various points, the past. They've exploded in popularity (much like podcasts), hoping that individual creators can find enough people to subscribe to keep them afloat (much like podcasts). It's an idea that can certainly work, though I doubt whether all of the newsletters out there today are going to survive, say, next year, much less in the next 5. (Much like ... well, you get it.) My inbox got to the point where I could find literally dozens of new issues on Sunday, and several more during each day of the week. They were unmanageable on their own, and they were crowding out my legitimate email.

In a perfect world, I could just subscribe to them in Feedly. I am an unabashed RSS reader, with somewhere in the vicinity of 140 active feeds. I am such a hardcore RSS addict that I subscribed to Feedly Pro lifetime somewhere in the vicinity of ... 2013, I think. Gods. It was a great deal ($99), but it means that I miss out on some of the new features, including the ability to subscribe to newsletters. There are also some services out there that seem like they do a relatively good job, but even at $5/month, that's $5 I'm not sending to a writer.

And frankly, I was pretty sure I could build it myself.

Thus was born Newslurp. It's not pretty. I will 100% admit that. The admin interface can be charitably described as "synthwave brutalist." That's because you really shouldn't spend any time there. The whole point is to set it up once and never have to touch the thing again. The interface really only exists so that you can check to see if a specific newsletter was processed.

It's not perfect. There are some newsletters that depend on a weirdly large amount of formatting, and more that have weird assumptions about background color. I've tried to fix those as I saw them, but there are a lot more mistakes out there than I could ever fix. Hopefully they include a "view in browser" link.

Setup is pretty easy.

-

Install dependencies using Composer

-

Use the SQL file in install.sql to create your database

-

Set up your Google API OAuth 2 Authenticaton. Download the client secret JSON file, rename it "client_secret.json" and put it in the project root

-

Navigate to your URL and authenticate using your credentials

-

Set up a filter in your Gmail account to label the emails you want to catch as "Newsletters." You can archive them, but do not delete them (the program will trash them after processing)

-

Visit /update once to get it started, then set up a cron to hit that URL/page however frequently you'd like

That's ... that's pretty much it, actually. It worked like a charm till I started using Hey (which has its own system for dealing with newsletters, which I also like). But it still runs for those of you out there in Google-land. Go forth and free your newsletters!

Loogit me, building the Substack app 3 years too early. And without the infrastructure. OK, I built an RSS feed. But I still saw the newsletter boom coming!

I have used WordPress for well over a decade now, for both personal and professional projects. WordPress was how I learned to be a programmer, starting with small modifications to themes and progressing to writing my own from scratch. The CMS seemed to find a delicate balance between being easy to use for those who weren't particularly technically proficient (allowing for plugins that could add nearly anything imaginable), while also allowing the more developer-minded to get in and mess with whatever they wanted.

I would go as far as to call myself a proselytizer, for a time. I fought strenuously to use it at work, constantly having to overcome the "but it's open-source and therefore insecure!" argument that every enterprise IT person has tried for the past two decades. But I fought for it because a) I knew it, so I could get things done more quickly using it, and b) it did everything we wanted it to at no cost. Who could argue against that?

The problems first started around the WordPress API. Despite an upswell of support among developers, there was active pushback by Matt Mullenweg, in particular, about including it in Core and making it more widely available - especially confusing since it wouldn't affect any users except those that wanted to use it.

We got past it (and got the API into core, where it has been [ab]used by Automattic), but it left a sour taste in my mouth. WordPress development was supposed to be community-driven, and indeed though it likely would not exist in its current state without Automattic's help, neither would Automattic have been able to do it all on its own. But the community was shut out of the decision-making process, a feeling we would get increasingly familiar with. Completely blowing the up the text editor in favor Gutenberg, ignoring accessibility concerns until an outside third-party paid for a review ... these are not actions of product that is being inculcated by its community. It's indicative of a decision-making process that has a specific strategy behind it (chasing new users at the expense of existing users and developers).

Gutenberg marked the beginning of the end for me, but I felt the final break somewhere in the 5.x.x release cycle when I had to fix yet another breaking change that was adding a new feature that I absolutely did not need or want. I realized I was not only installing plugins were actively trying to keep changes at bay, I was now spending additional development time just to make sure that existing features kept working. It crystallized my biggest problem I'd been feeling: WordPress is no longer a stable platform. I don't need new; I can build new. I need things to keep working once they're built. WordPress no longer provides that.

And that's fine! I am not making the argument that Automattic should do anything other than pursue their product strategy. I am not, however, in their target market, so I'm going to stop trying to force it.

A farewell to a CMS that taught me how to program, and eventually how to know when it's time to move on.