Almost everyone thinks they’re acting rationally. No matter how illogical (or uneven unhinged) an action may appear to outsiders, there’s almost always an internal logic that is at least understandable to the person making that decision, whether it’s an individual or an organization.

And it’s especially apparent in organizations. How many times has a company you liked or respected at one time made a blunder so mystifying that even you, as a fan, have no idea what could possibly have caused the chain of events that led to it? Yet if you were to ask the decision-makers, the reasoning is so clear they’re baffled as to why everyone is not in total lockstep with them.

There are any number of reasons why something that’s apparent to an outsider might be opaque to an insider, and I won’t even try to go over all of them. Instead, I want to focus on a specific categorical error: the misuse of data to drive decisions and outcomes.

A lot of companies say they are data-driven. Who wouldn’t want to be? The implication is that the careful, judicious analysis of data will yield only perfectly logical outcomes as to a company’s next steps or long-term plan. And it’s true that the use of data to inform your judgment can lead to better outcomes. But it can also lead to bad outcomes, for any number of reasons that we’ll discuss below.

But first, definitions.

Data: Individual, separate facts. These tend to be qualitative – if quantitative, they tend to be reduced to qualitative data for analysis.

Story: Connective framework for linking and explaining data.

Narrative: A well-reasoned story that tries to account for as much of the data and context as possible. It is entirely possible (and, in most cases, probable) that multiple narratives can be drawn from the same set of data. Narratives should have a minimum of assumptions, and all assumptions and caveats should be explicitly stated.

Fairytale: A story that is unsupported by the data, connecting data that does not relate to one another or using false data.

I have worked in a number of different industries, all of which pull different kinds of data and analytics to inform different aspects of their business. I cannot thing of a single one that avoided writing fairytales, though some were better systemically than others. What I’m going to do in this blog is go over a number of the different pitfalls you can fall into when writing stories that lead you astray from narrative to fairytale, and how you can overcome them.

I’ll try to use at least one real-world example for each so you can hopefully see how these same types of errors might crop up in your own owrk.

Why fairytales get written

1. Inventing or inferring explanations for specific data

I used to work in daily newspapers back when that was still thought to be a viable enterprise on the internet. The No. 1 problem (as I’m sure you’ve seen looking at any news site) is the chasing of a trend. A story would come across our analytics dashboard that appeared to be “doing numbers,” so immediately the original writer (and, often, a cabal of editors) would convene to try to figure out why that particular story had gone viral.

Oftentimes the real reason was something as ultimately uncontrollable as “we happened to get in the Google News carousel for that story” or “we got linked from Reddit” – phenomena that were not under our control. But because our mandate was to get big numbers, we would try to tease out the smallest things. More stories on the same topic, maybe ape the style (single-sentence paragraphs), try to time stories to go out at the same time every day …

It’s very similar to a cargo cult – remote villages who received supply drops during WWII came to believe that such goods were from a cargo “god,” and by following the teachings of a cargo “leader” (which typically involved re-enacting the steps that led up to the first drops, or mimicking European styles and activities) the cargo would return in abundance. When, in reality, the actions of the native peoples had little to no effect on whether more cargo would come.

This commonly happens when you’re asked to explain the reason for a trend or an outcome, a “why” about user behavior. It is nearly impossible to know why a user does something absent them explicitly telling you either through asynchronous feedback or user interviews. Everything else is conjecture.

But we’re often called upon (as noted above) to make decisions based on these unknowable reasons. What to do?

The correct way to handle these types of questions is:

-

Be clear that an explanation is a guess.

-

Treat that guess as a hypothesis.

-

Test that hypothesis.

-

Allow for the possibility that it’s wrong or that there is no right answer, period.

2. Load-bearing single data point

I see this all the time in engineering, especially around productivity metrics. There is an eternal debate as to whether you can accurately measure the productivity of a development team; my response to this is, “kinda.” You can measure any number of metrics that you want in order, but those metrics only measure what they measure. Most development teams use story points in order to gauge roughly how long a given chunk of development will take. Companies like to measure expected vs. actual story points, and then make actions based on those numbers.

Except that the spectrum of actions one can take based on those numbers is unknowably vast, and those numbers in and of themselves don’t mean anything. I worked on a development team where the CTO was reporting velocity up the chain to his superiors as a measure of customer value that was being provided. That CTO also refused to give story point assignments to bug tickets, since that wasn’t “delivering customer value.” I don’t know what definition of customer value you use in your personal life, but to me “having software that works properly” is delivering value.

But because bugs weren’t pointed, they were given lower priority (because we had to meet our velocity numbers). This increased focus on velocity numbers meant that tickets were getting pushed through to production without having gone through thorough testing, because the important thing was to deliver “customer value.” This, as you can imagine, led to more bug tickets that weren’t prioritized, rinse and repeat, until the CTO was let go and the whole initiative was dramatically restructured because our customers, shockingly enough, didn’t feel they were getting enough value in a broken product.

I want to introduce you to two of my favorite “laws” that I use frequently. The first, from psychology, is called Campbell’s Law, after the man who coined it, Donald Campbell. It states:

- The more emphasis you put on a data point for decision-making, the more likely it will wind up being gamed.

We saw this happen in a number of different ways. When story points got so important, suddenly story point estimates started going way up. Though we had a definition of done that including things like code review and QA testing, those things weren’t tracked or considered analytically, so they were de-emphasized when it was perceived that including them would hurt the number. Originally, the velocity stood for “number of story points in stories that were fully coded, tested and QA’ed.” By the end, they stood for “the maximum number of points we could reasonably assign to the stories that we rushed through at the end of the week to make velocity go up.”

The logical conclusion of Campbell’s Law is Goodhart’s Law, named after economist Charles Goodhart:

- When a measure becomes a target, it ceases to be a good measure.

Now, I am not saying you should ignore SPACE or DORA metrics. They can provide some insight into how your development / devops team is functioning. But you should use any of them, collectively or individually, as targets that you need or should meet. They are quantitative data that should be used in conjunction with other, qualitative, data garnered from talking and listening to your team. If someone’s velocity is down over a number of weeks, don’t go to them demanding it come up. Instead, talk to them and find out what’s going on. Have they noticed? Are they doing something differently?

My personal story point numbers tend to be all over the place, because some weeks my IC time is spent powering through my own stories, but then for months at a time I will devote the majority of my time to unblocking others or serving as the coordinator / point person for my team so they can spend their time head-down in the code. If you measured me solely by story points, I would undoubtedly be lacking. But the story points don’t capture all the value I bring to a team.

3. Using data because it’s available

This is probably the number one problem I see in corporate environments. We want to know the answer to x question, we have y data, so we’re going to use y to answer x even if the two are only tangentially (or, sometimes not even that closely) related.

I co-managed the web presence for a large research institution’s college of medicine. On the education side, our number one goal was to increase the quality and number of qualified applicants for our various programs. Except, on the web, it’s kind of hard to draw a direct line between “quality of website” and “quality of applicants.” Sure, if we got lucky someone would actually go through our website to the student application form, and we could see that in the analytics. But much like any major life decision, people made the decision to apply or not after weeks or months of deliberation, visiting the site sporadically. This, in addition to any number of other factors in their life that might affect their choice.

But you have to have KPIs, else how would you know that your workers aren’t slacking? So the powers that be decided the most salient data point was “number of visitors from the surrounding geographic area,” as measured by the geographic identification in Google Analytics (back when GA was at least pretending to provide useful data).

Now, some useful demographic information for you, the listener, to know is that in the year that mandate started being enforced, 53% of the incoming MD class was in-state. So, at best, our primary metric affected very slightly over half of our applicants to our flagship program. That’s to say nothing of the fact that people looking on the website might also just be members of the general public (since the college of medicine was colocated with a major hospital). It’s also not even true, if we were somehow able to discern who of the visitors were high-value applicants, that the website had anything to do with them applying or not to the program! That’s just not something you accurately track through analytics.

This is not an uncommon phenomenon. Because they had a given set of quantitative data to work with, that was the data they used to answer all the questions that were vital to the business.

I get it! It’s hard to say “no” or “you can’t” or “that’s impossible” to your boss when you’re asked to give information or justification. But that is the answer sometimes. The way to get around it is to 1) identify the data you’d actually need to answer the question, and 2) devise a method for capturing that data.

I also want to point out that it is vital to collect data with intent. Not intent as in “bias your data to the outcome you want,” but in the sense that you need to know what questions you’re going to ask of the data in order to be assured you’re collecting the right data. Going back after the fact to interrogate the data with different answers veers dangerously close to p-hacking, where you keep twisting and filtering data until you get some answer to some question, even if it’s not even close to the question you started with.

4. Discounting other possible explanations

I once sat in on a meeting where they were trying to impart to us the importance of caution. They told us about the story of Icarus; in Ancient Greece, the great inventor Daedalus was imprisoned in the Labyrinth he had built for the minotaur. Desperate to escape, he fashioned a set of wings from candle wax and feathers for him and his son, Icarus. Before leaving, he warned Icarus not to fly too close to the sea (for fear the spray would weigh down the wings and cause them to crash) nor too close to the sun, for the heat would melt the wax and cause them to crash. The pair successfully escaped the Labyrinth and the island, but Icarus, caught up in the exhilaration of flight, soared ever higher … until his wings melted and he came crashing down to the sea and drowned.

We were asked to reflect on the moral of the story. “The importance of swimming lessons!” I cracked, “Or, more generally, the importance of always having a backup plan.” Because, of course, Daedalus was worried that his son would fly too high or too low; rather than prepare for that possibility by teaching him how to swim (or fashioning a boat), Daedaelus did the bare minimum and caught the consequences.

Both my explanation and the traditional, “don’t fly too close to the sun” are valid takeaways; this is what I mean when I say that multiple valid narratives can arise from the same set of facts. Were we presenting a report to Daedalus, Inc., on the viability of his new AirWings, I would argue the most useful thing to do would be to present both. Both provide plausible outcomes and actionable information that can be taken away to inform the next stages of the product.

On a more realistic note, I was once asked to do an after-action analysis of a network incursion. In my analysis, I pointed out which IP ranges were generally agreed to be from the same South American country (where there was no legitimate business activity for the targeted company); those access logs seemed to match up with suspicious activity in Florida as well as another South Asian country.

I did not tie those things together. I did not state that they were definitively working together, or even knew of one another. I laid out possibilities including a coordinated attack by the Florida and South American entities (based on timestamps and accounts used); I also posited it was possible the attack originated in South Asia and they passed the compromised credentials to their counterparts (or even sold them to another group) in South America/Florida. It’s also possible that they were all independent actors either getting lucky or acting on the same tip.

The important thing was to not assume facts I did not (and could not) know, and make it very clear when I was extrapolating or assuming facts I did not have. One crucial difference between fairytale and narrative is the acknowledgment of doubt. Do not assert things you cannot know, and point out any caveats or assumptions you made in the formulation of your story. This will not only protect your reputation should any of those facts be wrong, but it makes it easier for others to both conceive of other, additional narratives you might not have, and leaves room / signposts as to what data might be collected in order to verify underlying assumptions.

Summary

It can be easy to get sucked into writing a fairytale when you started out writing a narrative. Data can be hard, deadlines can be short and pressure can be immense. Do you what you can to make sure you’re collecting good data with intent, asking and answering questions that are actually relevant to that data, and not discounting other explanations just because you finished yours. Through the application of proper data analysis, we can get better at providing good products to our customers and treating employees with respect and compassion while still maintaining productivity. It just requires diligence and a willingness to explore beyond superficial numbers to ensure the data you’re analyzing is accurately reflecting reality.

The best thing about this talk is it travels really well: People in Australia were just as annoyed by their companies' decision-making as those in the US.

Software requirements are rather straightforward - if we look at the requirements document, we see simple, declarative statements like "Users can log out," or "Users can browse and create topics." And that's when we're lucky enough to get an actual requirements document.

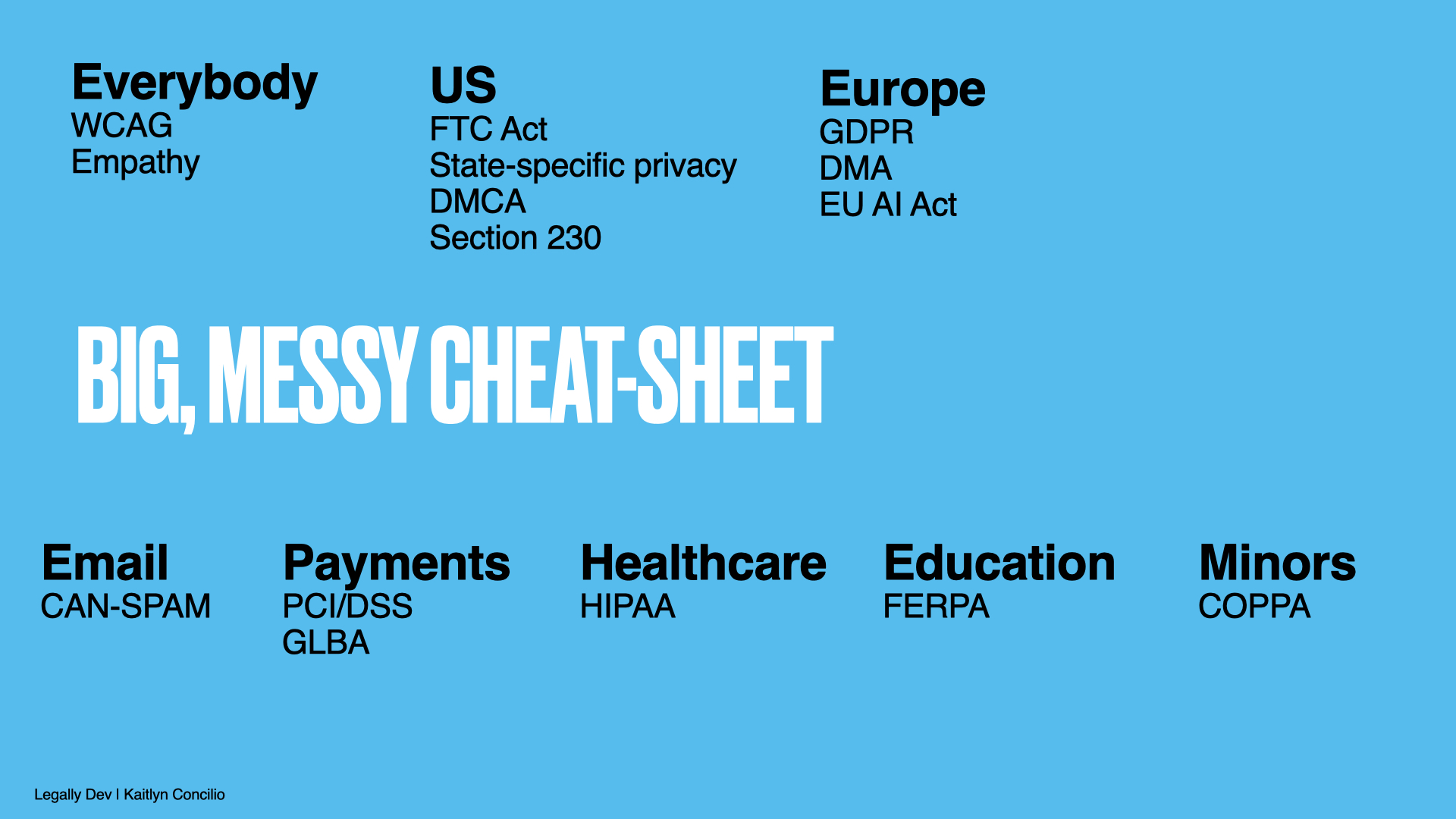

This is not legal advice

None of the following is intended to be legal advice. I am not a lawyer, have not even read all that many John Grisham novels, and am providing this as background for you to use. If you have actual questions, please take them to an actual lawyer. (Or you can try calling John Grisham, but I doubt he'd pick up.)

But there are other requirements in software engineering that aren't as cut-and-dried. Non-functional requirements related to things like maintainability, security, scalability and, most importantly for our purposes, legality.

For the sake of convenience, we're going to use "regulations" and other derivations of the word to mean "all those things that carry the weight of law," be they laws, rules, directives, court orders or what have you.

Hey, why should I care? Isn't this why we have lawyers?

Hopefully your organization has excellent legal representation. Also hopefully, those lawyers are not spending their days watching you code. That's not going to be fun for them or you. You should absolutely use lawyers as a resource when you have questions or aren't sure if something would be covered under a specific law. But you have to know when to ask those questions, and possess enough knowledge when your application could be running afoul of some rule or another.

It's also worthwhile to your career to know these things! Lots of developers don't, and your ability to point them out and know about them will make you seem more knowledgeable (because you are!). It will also make you seem more competent and capable than another developer who does not – again, because you are! This stuff is a skillset just like knowing Django.

While lawyers may be domain experts, they aren't always (especially at smaller organizations) and there are lots of regulations that specifically cover technology/internet-capable software that domain experts likely would not (and should not) be expected to be on top of. Further, if you are armed with foreknowledge, you don't have to wait for for legal review after the work has been completed.

Also, you know, users are people, too. Most regulations wind up being bottom-of-the-barrel expectations that user data is safeguarded and restricting organizations from tricking users into doing things they wouldn't have otherwise. In the same way I would hope my data and self-determination are respected, I also want to do the same for my users.

Regulatory environments

The difference in the regulatory culture between the US and the European Union is vast. I truly cannot stress how different they are, and that's an important thing to know about because it can be easy to become fluent in one and assume the other is largely the same. It's not. Trust me.

United States

The US tends, for the most part, to be a reactionary regulator. Something bad happens, laws or rules (eventually) get written to stop that thing from happening again.

Also, the interpretations of those rules tend to fluctuate more than in the EU, depending on things seemingly as random as which political party is in power (and controlling the executive branch, specifically) or what jurisdiction a lawsuit is filed in. We will not go in-depth into those topics, for they are thorny and leave scars, but it's important to note. The US also tends to give wide latitude to the defense of, "but it's our business model!" The government will not give a full pass on everything, but they tend to phrase things in terms of "making fixes" rather than "don't do that."

Because US regulations tend to be written in response to a specific incident or set of incidents, they tend for the most part to be very narrowly tailored or very broad ("e.g., TikTok is bad, let's give the government the ability to jail you for 20 years for using a VPN!"), leaving little guidance to those of us in the middle. This leaves lots of room for unintended consequences or simply failing to achieve the stated goals. In 2003, Congress passed the CAN-SPAM Act to "protect consumers and businesses from unwanted email." As anyone who ever looks at their spam box can attest, CAN-SPAM's acronym unfortunately seems to have meant "can" as in "grant permission," not "can" as in "get rid of."

European Union

In contrast, the EU tends to issue legislation prescriptively; that is, they identify a general area of concern, and then issue rules about both what you can and cannot do, typically founded in some fundamental right.

This technically is what the US does on a more circumspect level, but the difference is the right is the foundational aspect in the EU, meaning it's much more difficult to slip through a loophole.

From a very general perspective, this leads to EU regulations being more restrictive in what you can and can't do, and the EU is far more willing to punish punitively those companies who run afoul of the law.

Global regulations

There are few regulations that apply globally, and usually they come about backwards - in that a standard is created, and then adopted throughout the world.

Accessibility

In both the US and the EU, the general standard for digital accessibility is WCAG 2.1, level AA. If your website or app does not meet (most) of that standard, and you are sued, you will be found to be out of compliance.

In the US, the reason you need to be compliant comes from a variety of places. The federal government (and state governments) need to be compliant because of the Rehabilitation Act of 1974, section 508. Entities that receive federal money (including SNAP and NSF grants) need to be compliant because of the RA of 1974, section 504. All other publicly accessible organizations (companies, etc.) need to have their websites compliant because of the Americans with Disabilities Act and various updates. And all of the above has only arisen through dozens of court cases as they wound their way through the system, often reversing each other or finding different outcomes with essentially the same facts. And even then, penalties for violating the act are quite rare, with the typical cost being a) the cost of litigation, and b) the cost of remediation and compliance (neither of which are small, but they're also not punitive, either).

In the EU, they issued the Web Accessibility Directive that said access to digital information is a right that all persons, including those with disabilities, should have, so everything has to be accessible.

See the difference?

WCAG provides that content should be

-

Perceivable - Your content should be able to be consumed in more than one of the senses. The most common example of this is audio descriptions on videos (because those who can't see the video still should be able to glean the relevant information from it).

-

Operable - Your content should usable in more than one modality. This most often takes the form of keyboard navigability, as those with issues of fine motor control cannot always handle a mouse dextrously.

-

Understandable - Your content should be comprehensible and predictable. I usually give a design example here, which is that the accessibility standard actually states that your links need to be perceivable, visually, as links. Also, the "visited" state is not just a relic of CSS, it's actually an accessibility issue for people with neurological processing differences who want to be able to tell at a glance what links they've already been to.

Robust - Very broadly, this tenet states you should maximize your compliance with accessibility and other web standards, so that current and future technologies can take full advantage of them without requiring modification to existing content.

Anyway, for accessibility, there's a long list of standards you should be meeting. The (subjectively) more important ones most frequently not followed are:

-

Provide text alternatives for all non-text content: This means alt text for images, audio descriptions for video and explainer text for data/tables/etc. Please also pay attention to the quality – the purpose of the text is to provide a replacement for when the non-text content can't be viewed, so "picture of a hat" is probably not an actual alternative.

-

Keyboard control/navigation: Your site should be navigable with a keyboard, and all interactions (think slideshows, videos) should be controllable by a keyboard.

-

Color contrast: Header text should have a contrast ratio of 3:1 between the foreground and background; smaller text should have a ratio of 4.5:1.

-

Don't rely on color for differentiation: You cannot rely solely on color to differentiate between objects or types of objects. (Think section colors for a newspaper website: You can't just have all your sports links be red, it has to be indicated some other way.)

-

Resizability: Text should be able to be resized up to 200% larger without loss of content or functionality

-

Images of text: Don't use 'em.

-

Give the user control: You can autoplay videos or audio if you must, but you also have to give the user the ability to stop or pause it.

There are many more, but these are the low-hanging fruit that lots of applications still can't manage to pick off

PCI DSS

The Payment Card Industry Data Security Standard is a set of standards that govern how you should store credit card data, regulated by credit card companies themselves. Though some individual US states require adherence to the standards (and fine violators appropriately), federal and EU law does not require you to follow these standards (at least, not specifically these standards). However, the credit card companies themselves can step in and issue fines or, more critically, cut off access to their payment networks if they find the breaches egregious enough.

In most cases, organizations offload their payment processing to a third party (e.g., Stripe, Paypal), who is responsible for maintaining compliance with the specification. However, you as the merchant or vendor need to make sure you’re storing the data from those transactions in the manner provided by the payment processor; it’s not uncommon to find places that are storing too much data on their own infrastructure that technically falls under the scope of PCI DSS.

Some of the standards are pretty basic - don’t use default vendor passwords on hardware and software, encrypt your data transmissions. Some are more involved, like restricting physical access to cardholder data, or monitoring and logging access to network resources and data.

EU regulations

GDPR

The EU's General Data Privacy Regulation caused a big stir when it was first released, and for good reason. It completely changed the way that companies could process and store user data, and severely restricted what sort of shenanigans companies can get up to.

The GDPR states that individuals have the right to not have their information shared; that individuals should not have to hand over their information in order to access goods or services; and that individuals have further rights to their information even once it's been handed over to another organization.

For those of us on the side of building things, it means a few things are now requirements that used to be more "nice-to-haves."

-

You must get explicit consent to collect data If you're collecting data on people, you have to explicitly ask for it. You have to specify exactly what information you're collecting, the reason you're collecting it, how long you plan on storing it and what you plan to do with it (this is the reason for the proliferation of all those cookie banners a few years ago). Furthermore, you must give your users the right to say no. You can't just pop up a full-screen non-dismissable modal that doesn't allow them to continue without accepting it.

-

You can only collect data for legitimate purposes Just because someone's willing to give you data doesn't mean you're allowed to take it. One of my biggest headaches I got around GDPR was when a client wanted to gate some white papers behind an email signup. I patiently explained multiple times that you can't require an email address for a good or service unless the email address was required to provide said good or service. No matter how many times the client insisted that he had seen someone else doing the same thing, I stood firm and refused to build the illegal interaction.

-

Users have the right to ask for the data you have stored, and to have it deleted Users can ask to see what data you have stored on them, and you're required to provide it (including, again, why you have that data stored). And, unless it's being used for legitimate processing purposes, you have to delete that data if the user requests it (the "right to be forgotten").

And all of this applies to any organization or company that provides a good or service to any person in the EU. Not just paid, either – it explicitly says that you do not have to charge money to be covered under the GDPR. So if your org has an app in the App Store that can be downloaded in Ireland, Italy, France or any other EU country, it and likely a lot more of your company's services will fall under GDPR.

As for enforcement, organizations can be fined up to €20 million, or up to 4% of the annual worldwide turnover of the preceding financial year, whichever is greater. Amazon Europe got docked €746 million for what was alleged "[manipulation of] customers for commercial means by choosing what advertising and information they receive[d]" based on the processing of personal data. Meta was fined a quarter of a billion dollars a few different times.

But it's not just the big companies. A translation firm got hit with fines of €20K for "excessive video surveillance of employees" (a fine that's practically unthinkable in the US absent cameras in a private area such as the bathroom), and a retailer in Belgium had to pay €10K for forcing users to submit an ID card to create a loyalty account (since that information was not necessary to creating a loyalty account).

Digital Markets Act

The next wave of regulation to hit the tech world was the Digital Markets Act. which is aimed specifically at large corporations that serve a “gatekeeping functionality” in digital markets in at least three EU countries. Although it is not broadly applicable, it will change the way that several major platforms will work with their data.

The directive’s goal is to break up the oversized share that some platforms have in digital sectors like search, e-commerce, travel, media streaming, and more. When a platform controls sufficient traffic in a sector, and facilitates sales between businesses and users, it must comply with new regulations about how data is provisioned and protected.

Specifically, those companies must:

-

Allow third parties to interoperate with their services

-

Allow businesses to access the data generated on the platform

-

Provide advertising partners with the tools and data necessary to independently verify claims

-

Allow business users to promote and conduct business outside of the platform

Additionally, the gatekeepers cannot:

-

Promote internal services and products over third parties

-

Prevent consumers from linking up with businesses off their platforms

-

Prevent users from uninstalling preinstalled software

-

Track end users for the purpose of targeted advertising without users’ consent

If it seems like these are aimed at the Apple App Store and Google Play Store, well, congrats, you cracked the code. The DMA aims to help businesses have a fairer environment in which to operate (and not be completely beholden to the gatekeepers), and allow for smaller companies to innovate without being hampered or outright squashed by established interests.

US regulations

The US regulatory environment is a patchwork of laws and regulations written in response to various incidents, and with little forethought for the regulatory environment as a whole. It’s what allows you as a developer to say, “Well, that depends …” in response to almost any question, to buy yourself time to research the details.

HIPAA

Likely the most well-known US privacy regulation, HIPAA covers almost none of the things that most people commonly think it does. We'll start with the name: Most think it's HIPPA, for Health Information Privacy Protection Act. It actually stands for Healthcare Insurance Portability and Accountability Act, because most of the law has nothing to do with privacy.

It is very much worth noting that HIPAA only applies to health plans, health care clearinghouses, and those health care providers that transmit health information electronically in connection with certain administrative or financial transactions where health plan claims are submitted electronically. It also applies to contractors and subcontractors of the above.

That means most of the time when people publicly refuse to comment on someone's health status because of HIPAA (like, in a sports context or something), it's nonsense. They're not required to disclose it, but it's almost certainly not HIPAA that's preventing them from doing so.

What is relevant to us as developers is the HIPAA Privacy Rule. The HIPAA privacy rule claims to "give patients more control over their health information, set boundaries on the use of their health records, establish appropriate safeguards for the privacy of their information."

What it does in practice is require that you have to sign a HIPAA disclosure form for absolutely every medical interaction you have (and note, unlike GDPR, that they do not have to let you say "no"). Organizations are required to keep detailed compliance policies around how your information is stored and accessed. While the latter is undoubtedly a good thing, it does not rise to the level of reverence indicated by its stated goals.

What you as a developer need to know about HIPAA is you need to have very specific policies (think SOC II [official link] [more useful link]) around data access, operate using the principle of least privileged access (only allow those who need to see PHI to be able to access it), and specific security policies related to the physical facility where the data is stored.

HIPAA’s bottom line is that you must keep safe Protected Health Information (PHI), which covers both basic forms of personally identifiable information (PII) such as name, email, address, etc., as well as any health conditions those people might have. This seems like a no-brainer, but it can get tricky when you get to things like disease- or medicine-specific marketing (if you’re sending an email to someone’s personal email address on a non-HIPAA-compliant server about a prostate cancer drug, are you disclosing their illness? Ask your lawyer!).

There are also pretty stringent requirements related to breach notifications (largely true of a lot of the compliance audits as well). These are not things you want to sweep under the rug. It’s true that HIPAA does not see many enforcement acts around the privacy aspects as some of the other, jazzier regulations. But health organizations also tend to err on the side of caution and use HIPAA-certified hosting and tech stacks, as any medical provider will be sure to complain about to you if you ask them how they enjoy their Electronic Medical Records system.

Section 230 of the Communications Decency Act

Also known as the legal underpinnings of the modern internet, Section 230 provides that "No provider or user of an interactive computer service shall be treated as the publisher or speaker of any information provided by another information content provider."

In practice, this means that platforms that publish user-generated content (UGC) will not be treated as the "publisher," in the legal sense, of that content for the purposes of liability for libel, etc. This does not mean they are immune from copyright or other criminal liabilities but does provide a large measure of leeway in offering UGC to the masses.

It's also important to note the title of the section, "Protection for private blocking and screening of offensive material." That's because Section 230 explicitly allows for moderation of private services without exposing the provider to any liability for failing to do so in some instances. Consider a social media site that bans Nazi content; if that site lets a few bad posts go through, it does not mean they are on the hook for those posts, at least legally speaking. Probably a good idea to fix the errors lest they be found guilty in the court of public opinion, though.

GLBA

The Graham-Leach-Biley Act is a sort of privacy protection policy for financial institutions. It doesn’t lay out anything particular novel or onerous - financial institutions need to provide a written privacy policy (what data is collected, how it’s used, how to opt-out), and provides some guidelines companies need to meet about safeguarding sensitive customer information. The most interesting, to me, requirement is Pretext Protection, which actually enshrines in law that companies need to have policies in place for how to prevent and mitigate social engineering attacks, both of the phishing variety as well as good old-fashioned impersonation.

COPPA

The Children's Online Privacy Protection Rule (COPPA, and yes, it’s infuriating that the acronym doesn’t match the name) is one of the few regulations with teeth, largely because it is hyperfocused on children, an area of lawmaking where overreaction is somewhat common.

COPPA provides for a number of (now) common-sense rules governing digital interactions that companies can have with children under 13 years old. Information can only be collected with:

-

Explicit parental consent.

-

Separate privacy policies must be drafted and posted for data about those under 13.

-

A reasonable means for parents to review their children's data.

-

Establish and maintain procedures for protecting that data, including around sharing that data.

-

Limits on retention of that data.

-

Prohibiting companies from asking for more data than is necessary to provide the service in question.

Sound weirdly familiar, like GDPR? Sure does. Wondering why only children in the US are afforded such protections? Us too!

FERPA

The Family Educational Rights Protection Act is sort of like HIPAA, but for education. Basically, it states that the parents of a child have a right to the information collected about their child by the school, and to have a say in the release of said information (within reason; they can't squash a subpoena or anything). When the child reaches 18, those rights transfer to the student. Most of FERPA comes down to the same policy generation around retention and access discussed in the section on HIPAA, though the disclosure bit is far more protective (again, because it's dealing with children).

FTC Act

The Federal Trade Commission Act of 1914 is actually the law that created the Federal Trade Commission, and the source of its power. You can think of the FTC as a quasi-consumer protection agency, because it can (and, depending on the political party in the presidency, will) go after companies for what aren't even really violations of law so much as they are deemed "unfair." The FTC Act empowers the commission to prevent unfair competition, as well as protect consumers from unfair/deceptive ads (though in practice, this has been watered down considerably by the courts).

Nevertheless, of late the FTC has been on a roll, specifically targeting digital practices. An excellent recent example was the settlement by Epic Games, makers of Fortnite. The FTC sued over a number of allegations, including violations of COPPA, but it also explicitly called out the company for using dark patterns to trick players into making purchases. The company’s practice of saving any credit cards used (and then making that card available to the kids playing), confusing purchasing prompts and misleading offers were specifically mentioned in the complaint.

CAN-SPAM

Quite possibly the most useless technology law on the books, CAN-SPAM (Controlling the Assault of Non-Solicited Pornography And Marketing Act) clearly put more time into the acronym than the legislation. The important takeaways are that emails need:

-

Accurate subjects

-

To disclose themselves as an ad

-

Unsubscribe links

-

A physical address for the company

And as your spam box will tell you, it solved the problem forever. This does not, however, mean you can ignore its strictures! As a consultant at a company that presumably wishes to stay on the right side of the law, you should still follow its instructions.

CCPA and Its Ilk

The California Consumer Privacy Act covers, as its name suggests, California residents in their dealings with technology companies. Loosely based on the GDPR, CCPA requires that businesses disclose what information they have about you and what they do with it. It covers items such as name, social security number, email address, records of products purchased, internet browsing history, geolocation data, fingerprints, and inferences from other personal information that could create a profile about your preferences and characteristics.

It is not as wide-reaching or thorough as GDPR, but it’s better than the (nonexistent) national privacy law.

The CCPA applies to companies with gross revenues totaling more than $25 million, businesses with information about more than 50K California residents, or businesses who derive at least 50% of their annual revenue from selling California residents’ data. There are similar measures that have already been made law in Connecticut, Virginia, Colorado, and Utah, as well as other states also considering relevant bills.

Other state regulations

The joy of the United States’ federalist system is that state laws can be different (and sometimes more stringent!) than federal law, as we see with CCPA. It would behoove you to do a little digging into the state regulations when you’re working with specific areas — e.g., background checks, where the laws differ from state to state, as even though you’re not based there, you may be subject to its jurisdiction.

There are two different approaches companies can take to dealing with state regulations: Either treat everyone under the strictest regulatory approach (e.g., treat every user like they’re from California) or make specific carve-outs based on the state of residence claimed by the user.

It is not uncommon, for example, to have three or four different disclosures or agreements for background checks ready to show a user based on what state they reside in. The specific approach you choose will vary greatly depending on the type of business, the information being collected, and the relevant state laws.

How to implement

Data compliance is critical, and the punitive aspects of GDPR’s enforcement means your team must have a solid strategy for compliance.

The most important aspect of dealing with any regulatory issue is first knowing what’s required for your business. Yes, you’re collecting emails, but to what end? If that data is necessary for your business to function, then you have your base-level requirements.

Matching those up against the relevant regulations will provide you with a starting point from which you can begin to develop the processes, procedures and applications that will allow your business to thrive. Don’t rely on “that’s how we’ve always done it” or “we’ve seen other people do x” as a business strategy.

The regulatory environment is constantly shifting, and it’s important to both keep abreast of changes as well as always knowing what data and services are integral to your business’s success. Keeping up with the prevalent standards will aid you not only in not getting sued, but also ensuring your companies that you’re a trustworthy and reliable partner.

How to keep up

It all seems a little daunting, no?

But you eat the proverbial regulatory elephant the same way you do any other large food item: one bite at a time. In the same way you didn’t become an overnight expert in securing your web applications against cross-site scripting attacks or properly manage your memory overhead, becoming a developer who’s well-versed in regulatory environments is a gradual process.

Now that you know about some of the rules that may apply to you, you know what to keep an eye out for. You know potential areas to research when new projects are pitched or started, and you know where to ask questions. You know to both talk to and listen to your company’s legal team when they start droning on about legalistic terms

People always seem confused by the title of this: "What does scrum have to do with measuring productivity?" they ask. And I smile contentedly, because that's the whole point.

Scrum is supposed to be a system for managing product work, iterating and delivering value to the customer. What usually winds up happening is scrum gets used for the management of software development work as a whole, from decisions about promotion to hiring and firing to everything else. That's not what scrum is designed to do, and it shows.

Now, I love to talk about process improvement, completely agnostic of whatever process framework you're using. I would much rather have a discussion about the work you're doing and what blockers you're hitting rather than discussing abstract concepts.

However, if you keep running into the same issues and blockers over and over again, it's usually worth examining your workflows to find out if you're actually applying the theory behind your framework to the actual work you're doing. The concept of Agile specifically is not about the processes involved, but you need to know and understand the rules before you should feel comfortable breaking them.

Processes

I want to start with a quick overview of a few key terms to make sure everyone's on the same page.

- **Waterfall **

In waterfall development, every item of work is scheduled out in advance. This is fantastic for management, because they can look at the schedule to see exactly what should be worked on, and have a concrete date by which everything will done.

This is horrible for everyone, including management, because the schedule is predicated upon developers being unerring prophets who are able to forecast not only the exact work that needs to be done to develop a release, but also the exact amount of time said work will take.

The ultimate delimiter of the work to be done is the schedule - usually there’s a specific release date (hopefully but not always far out enough to even theoretically get all the work done); whatever can get done by that date tends to be what’s released.

Waterfall also suffers greatly because it’s completely inflexible. Requirements are gathered months ahead of time; any changes require completely reworking the schedule, so changes are frowned upon. Thus, when the product is released, it’s usually missing features that would have been extremely beneficial to have.

- Agile

Agile can be viewed as a direct response to waterfall-style development; rather than a rigid schedule, the agile approach embraces iteration and quick releases. The three primary “laws” of agile are:

- **Law of the customer** - The customer is the number one priority. Rather than focusing on hitting arbitrary milestones or internal benchmarks, agile teams should be focused on delivering products to customers that bring them additional value. A single line of code changed can be more worthwhile than an entirely new product if that line brings extra value to the customer.

-

Law of small teams - Developers are grouped into small teams that are given autonomy in how they implement the features they’re working on. When work is assigned to a team, it’s not done so prescriptively. In the best agile teams, the assignment is, “Here’s the problem we have, go solve it.”

-

Law of the network - There are differing interpretations on how to implement this, but essentially I view of the network as “the whole organization has to buy in to what the agile teams are doing.” The entire organization doesn’t need to have the same structure as the agile teams, but neither can it be structured in a manner antithetical to the processes or outcomes. The easiest counterexample is the entire dev department is using scrum, but the CTO still feels (by virtue of their title) the ability to step in and make changes or contribute code or modify stories on a whim. Just because the CTO is the manager doesn’t mean they have full control over every decision. Basically, law of the network means “respecting the agile method, even if you’re not directly involved.”

It’s worth noting that agile is a philosophy, not a framework in and of itself. Both kanban and scrum are implementations of the agile philosophy.

-

- **Kanban**

This is usually the most confusing, because both scrum and kanban can use kanban boards (the table of stories, usually denoted by physical or virtual “post-its” that represent the team’s work). Kanban board splits up work into different “stages” (e.g., to-do, doing, done), and provides a visual way to track progression of stories.

The primary difference between scrum and kanban as a product development methodology is that kanban does not have specific “sprints” of work - the delimiter of work is how many items are in a given status at a given time. For example, if team limits “doing” to four cards and there are already four cards in there, no more can be added until one is moved along to the next stage (usually this means developers will pair or mob on a story to get it through).

- **Scrum**

Scrum, by contrast, delimits its work by sprints. Sprints are the collection of work the team feels is necessary to complete to deliver value. They can be variable in their length (though in practice, they tend to be a specified time length, which causes its own issues).

Scrum requires each team to have at least two people - a product owner and a scrum master. Usually there are also developers, QA and devops people on the team as well, but at a minimum you need the PO and SM.

The product owner has the vision for what the product should be - they should be in constant contact with customers, potential customers and former customers to figure out how value can be added. The scrum master’s job is to be the sandpaper for the developers - not (as the name implies) their manager or boss, but the facilitator for ceremonies and provide coaching/guidance on stories and blockers.

I will note that a lot of the reasons I will list below may also apply to other product management methodologies; however, I’m specifically limiting the scope to how they impact scrum teams.

Lack of product vision

I don’t want to lay the blame entirely on product owners for this issue - very often the problem is with how the role is designed and hired for. Product owners should be the final arbiters for product decisions. They should absolutely consult design, UX and customer service experts for their opinions, but the decisions ultimately lies with them.

Unfortunately, the breadth of skills required to be a good product owner are not in abundant supply, and product owners are, bafflingly, often considered afterthoughts at many organizations.

More than specific skills, though, product owners need to have a vision for what the product could be, as well as the flexibility to adapt that vision when new information comes in. Usually, this requires domain knowledge (that can be acquired, but needs to be done so systematically and quickly upon hiring), steadfastness of conviction and the ability to analyze data properly to understand what customers want.

Far too often product owners essentially turn into feature prioitizers, regurgitating nearly everything customers say they want and assigning a ranking to it. This often comes at the expense of both the product’s conceptual integrity as well as relationships with developers, who are supposed to be given problems to solve, not features to develop. This is the classic feature factory trap.

Mistake the rules for the reason

Far too often, people will adopt the ceremonies or trappings of scrum without actually accepting an agile mindset. This is where my favorite tagline, “that’s just waterfall with sprints” comes from.

If you’ve ever started a project by first projecting and planning how long it’s going to take you to deliver a given set of features, congratulations, you’re using waterfall.

To use scrum, you need to adopt the iterative mindset to how you view your product. If you’re developing Facebook, you don’t say, “we’re going to build a system that allows you to have an activity feed that shows posts from your friends, groups and advertisters, and have an instant messaging product, and ..”

Instead, you’d say, “we’re going to develop a platform that helps people connect to one another.” Then you’d figure out the greatest value you can add in one sprint (e.g., users can create profiles and upload their picture.). You know once you have profiles you’ll probably want the ability to post on others’ profiles, so that’s in the backlog.

That’s it. That’s the planning you do. Because once those releases get into customers’ hands, you’ll then have better ideas for how to deliver the next increment of value.

Simply because an organization has “sprints” and a “backlog” and do “retros” doesn’t mean its’ using scrum, it means it’s using the language of scrum.

Lack of discipline/iteration

Tacking on to the last point, not setting up your team for success in an agile environment can doom the product overall. Companies tend to like hiring more junior developers, because they’re cheaper, but not realizing that a junior developer is not just a senior developer working at 80% speed. Junior developers need to have mentoring and code reviews, and those things take time. If the schedule is not set up to allow for that necessary training and code quality checks to happen, the product will suffer overall.

Similarly, development teams are often kept at a starting remove from everyday users and their opinions/feedback. While I by no means advocate a direct open firehose of feedback, some organizations don’t ever let their devs see actual users using the product, which creates a horrible lack of feedback loop from a UX and product design perspective.

Properly investing in the team and the processes is essential to any organization, but especially one that uses scrum.

Lack of organizational shift

The last ancillary reason I want to talk about in terms of scrum failure is aligning the organization with the teams that are using scrum (we’re back to the law of network, here). Scrum does not just rely on the dev team buying in, it also requires the larger organization to at least respect the principles of scrum for the team.

The most common example of this I see is when the entire dev department is using scrum, but the CTO still feels (by virtue of their title) the ability to step in and make changes or contribute code or modify stories on a whim. Just because the CTO is the manager doesn’t mean they have full control over every decision. Removing the autonomy for the team messes with the fundamental principles of scrum, and usually indicates there will be other issues as well (and I guarantee that CTO will also be mad when the scrum is now unbalanced or work doesn’t get done, even though they’re the direct cause).

No. 1 reason scrum fails: It’s used for other purposes

By far, the biggest reason I see scrum failing to deliver is when the ceremonies or ideas or data generated by scrum gets used for something other than delivering value to the end users.

It’s completely understandable! Management broadly wants predictability, the ability to schedule a release months out so that marketing and sales can create content and be ready to go.

But that’s not how scrum works. Organizations are used to being able to dictate schedules for large releases of software all at once (via waterfall), and making dev deliver on those schedules. If you’re scheduling a featureset six months out, it’s almost guaranteed you’re not delivering in an agile manner.

Instead of marketing-driven development, why not flip the script and have development-driven marketing? There is absolutely no law of marketing that says you have to push a new feature the second it’s generally available. If the marketing team keeps up with what’s being planned a sprint in an advance, that means they’d typically have at least a full month of leadtime to prepare materials for release.

Rather than being schedulable, what dev teams should shoot for is reliability and dependability. If the dev team commits to solving an issue in a given sprint, it’d better be done within that sprint (within reason). If it’s not, it’s on the dev team to improve its process so the situation doesn’t happen again.

But why does scrum get pulled off track? Most often, it’s because data points in scrum get used to mean something else.

Estimates

The two hardest problems in computer science are estimates, naming things, and zero-based indexes. Estimates are notoriously difficult to get right, especially when developing new features. Estimates get inordinately more complex when we talk about story pointing.

Story points are a value assigned to a given story. They are supposed to be relative to other stories in the sprint - e.g., a 2 is bigger than a 1, or a medium is bigger than a small, whatever. Regardless of the scale you’re using, it is supposed to be a measure of complexity for the story for prioritization purposes only.

Unfortunately, what usually winds up happening is teams adopt some sort of translation scale (either direct or indirect), something like 1 = finish in an afternoon, 2 = finish in a day, 3 = multiple days, 5 = a week, etc. But then management wants to make sure everyone is pulling their fair share, so people are gently told that 10 is the expectation for the number of points they should complete in a two-week sprint, and now we are completely off the rails.

Story points are not time estimates. Full stop.

It’s not a contract, you’re not a traffic cop trying to make your quota. Story points are estimates of the complexity of a story for you to use in prioritization. That’s it.

I actually dislike measuring sprint velocity sprint-to-sprint, because I don’t think it’s helpful in most cases. It actually distorts the meaning of a sprint. Remember, sprints are supposed to be variable in length; if your increment of value is small, have a small sprint. But because sprint review and retro have to happen every second Friday, sprints have to be two weeks. Because the sprint is two weeks, now we have two separate focii, and the scrum methodology drifts further and further away.

Campbell’s law is one of my favorite axioms. Paraphrased, it states:

The more emphasis placed on a metric, the more those being measured will be incentivized to game it.

In the case above, if developers are told they should be getting 10 points per sprint, suddenly their focus is no longer on the customer. It’s now on the number of story points they have completed. They may be disincentivized to pick up larger stories, fearing they might get bogged down. They’re almost certainly going to overestimate the complexity of stories, because now underestimates mean they’re going to be penalized in terms of hitting their targets.

This is where what I call the Concilio Corollary (itself a play on the uncertainty principle) comes into play:

You change the outcome of development by measuring it.

It’s ultimately a question of incentives and focus. If you start needing to worry about metrics other than “delivering value to the user,” then your focus drifts from same. This especially comes into play when organizations worry about individual velocity.

I don’t believe in the practice of “putting stories down” or “pick up another story when slightly blocked.” If a developer is blocked, it’s on the scrum master and the rest of the team to help them get unblocked. But I absolutely understand the desire to do so if everybody’s expected to maintain a certain momentum, and other people letting their tasks lie to help you is detrimental to their productivity stats. How could we expect teamwork to flourish in such an environment?

So how do we measure productivity?

Short answer: don’t.

Long answer: Don’t measure “productivity” as if it’s a value that can be computed from a single number. Productivity on its own is useless.

I used to work at a college of medicine, and after a big website refresh they were all excited reporting how many pageviews the new site was getting. And it makes sense, because when we think of web analytics, we think page views and monthly visitors and time on site, all that good stuff.

Except … what’s the value of pageviews to a college? They’re not selling ads, where more views works out to more money. In fact, the entire point of the website was to get prospective students to apply. So rather than track “how many people looked at this site,” what they should have been doing was looking at “how many come to this site and then hit the ‘apply now’ button,” and comparing that to the previous incarnation.

First, you need to figure out what the metrics are being used for. There are any number of different reasons you might want to measure “productivity” on a development team. Some potential reasons include performance reviews, deciding who to lay off, justifying costs, figuring out where/whether to invest more, or fixing issues on the development team.

But each of those reasons has a completely different dataset you should be using to make that decision. If you’re talking about performance reviews, knowing the individual velocity of a developer is useless. If it’s a junior, taking on a 5-point story might be a huge accomplishment. If you’re looking at a principal or a senior, you might actually expected a lower velocity, because they’re spending more time pairing with other developers to mentor them or help them get unblocked.

Second, find the data that answers the question. When I worked at a newspaper, we used to have screens all over the place that showed how many pageviews specific articles were getting. Except, we didn’t sell ads based on total pageviews. We got paid a LOT of money to sell ads to people in our geographical area, and a pittance for everything else. A million pageviews usually meant we had gone viral, but most of those hits were essentially worthless to us. To properly track and incentivize for best return, we should have been tracking local pageviews as our primary metric.

Similarly, if you’re trying to justify costs for your development team, just throwing the sprint velocity out there as the number to look at might work at the beginning, but that now becomes the standard you’re measured against. And once you start having to maintain features or fix bugs, those numbers are going to go down (it’s almost always easier to complete a high-point new-feature story than a high-point maintenance story, simply because you don’t have to understand or worry about as much context).

There are a number of newer metrics that have been proposed as standards that dev teams should be using. I don’t have an inherent problem with most of these metrics, but I do want to caution not to just adopt them wholesale as a replacement for sprint velocity. Instead, carefully consider what you’re trying to use the data for, then select those metrics that provide that data. Those metrics are SPACE and DORA. Please note that these are not all individual metrics; some of them (such as “number of handoffs”) are team-based.

SPACE

• Satisfaction and well-being

◦ This involves developer satisfaction surveys, analyzing retention numbers, things of that nature. Try to quantify how your developers feel about their processes.

• Performance

◦ This might include some form of story points shipped, but would also include things like number and quality of code reviews.

• Activity

◦ Story points completed, frequency of deployments, code reviews completed, or amount of time spent coding vs. architecting, etc.

• Communication/collaboration

◦ Time spent pairing, writing documentation, slack responses, on-call/office hours

• Efficiency/flow

◦ Time to get code reviewed, number of handoffs, time between acceptance and deployment

DORA

DORA, or DevOps Research and Assessment, are mostly team-based metrics. They include:

• Frequency of deployments

• Time between acceptance and deployment

• How frequently deployments fail

• How long it takes to recover/restore from failed

Focus on impact

But all of these metrics should be secondary, as the primary purpose of a scrum team is to deliver value. Thus, the primary metrics should measure direct impact of work: How much value did we deliver to customers?

This can be difficult to ascertain! It requires a lot of setup and analysis around observability, but these are things that a properly focused scrum team should already be doing. When the dev team is handed a story for a new feature, one factor of that story should be success criterion: e.g., at least 10% of active users use this feature in the first 10 days. That measurement should be what matters most. And failing to meet that mark doesn’t mean the individual developer failed, it means some underlying assumption (whether it’s discoverability or user need) is flawed, and should be corrected for the next set of iterations.

It comes down to outcome-driven-development vs. feature-driven-development. In scrum, you should have autonomous teams working to build solutions that provide value to the customer. That also includes accountability for the decisions that were made, and a quick feedback loop coupled with iteration to ensure that quality is being delivered continuously.

TL;DR

In summation, these are the important bits:

• Buy in up and down the corporate stack - structure needs to at least enable the scrum team, not work against it

• Don’t estimate more than you need to, and relatively at that

• Know what you’re measuring and why

Now, I know individual developers are probably not in a position to take action at the level “stop using metrics for the wrong reasons.” That’s why I have a set of individual takeaways you can use.

• Great mindset for performance review

◦ I am a terrible self-promoter, but keeping in mind the value I was creating made it easy for me come promotion time to say, “this is definitively what I did and how I added value to the team.” It made it much easier for me than trying to remember what specific stories I had worked on or which specific ideas were mine.

• Push toward alignment

◦ Try to push your leaders into finding metrics that answer the questions they’re actually asking. You may not be able to get them to abandon sprint velocity right off the bat, but the more people see useful, actionable metrics the less they focus on useless ones.

• Try to champion customer value

◦ It’s what scrum is for, so using customer value as your North Star usually helps cut through confusion and disagreement.

• Get better at knowing what you know / don't know

◦ This is literally the point of sprint retros, but sharing understanding of how the system works will help your whole team to improve the process and produce better software.

Since this post is long enough on its own, I also have a separate post from when I gave this talk in Michigan of questions people asked and my answers.

That's not REAL waterfall, it's just a babbling brook on a hill.

I grew up on Clean Code, both the book and the concept. I strove for my code to be “clean,” and it was the standard against which I measured myself.

And I don’t think I was alone! Many of the programmers I’ve gotten to know over the years took a similar trajectory, venerating CC along with Code Complete and Pragmatic Programmer as the books everyone should read.

But along the way, “clean” started to take on a new meaning. It’s not just from the context of code, either; whether in interior design or architecture or print design, “clean” started to arise as a synonym for “minimalism.”

This was brought home to me when I was working with a junior developer a couple years ago. I refactored a component related to one we working on together to enable necessary functionality, and I was showing him the changes. This was a 200-line component, and he skimmed it about 45 seconds before saying “Nice, much cleaner.”

And it bugged me, but I wasn’t sure why. He was correct - it was cleaner, but it felt like that shouldn’t have been something he was accurately able to identify simply by glancing at it. Or at least, if that was the metric he was using, “clean” wasn’t cutting it.

Because the fact of the matter is you can’t judge the quality of code without reading it and understanding what it’s trying to do, especially without considering it in the context of its larger codebase. You can find signifiers (e.g., fewer lines of code, fewer methods in a class), but “terse” is not a direct synonym of “clean.” Sometimes less code is harder to understand or maintain than more code.

I wanted to find an approach, a rubric, that allowed for more specificity. When I get feedback, I much prefer hearing the specific aspects that are being praised or need work on - someone telling me “that code’s clean” or not isn’t particularly actionable.

So now I say code should be Comprehensible, Predictable and Maintainable. I liked those three elements because they’re important on their own, but also each builds on the others. You cannot have predictable and maintainable code unless it’s also comprehensible, for example.

-

Comprehensible - People other than the author, at the time the code is written, can understand both what the code is doing and why.

-

Predictable - If we look at one part of the code (a method, a class, a module), we should be able to infer a number of properties about the rest.

-

Maintainable - Easy to modify and keep up, as code runs forever

Comprehensibility is important because we don’t all share the context - even if you’re the only person who’s ever going to read the code, the you of three weeks from now will have an entirely different set of issues you’re focusing on, and will not bring the same thoughts to bear when reasoning about the code. And, especially in a professional context, rare is the code that’s only ever read by one other person.

Predictability speaks to cohesion and replicability across your codebase. If I have a method load on a model responsible for pulling that object’s information from the database, all the other models should use load when pulling object info from the DB. Even though you could use get or loadFromDb or any number of terms that are still technically comprehensible, the predictability of using the same word to mean the same thing reduces overall cognitive load when reasoning about the application. If I have to keep track of which word means the action I’m trying to take based on which specific model I’m using, that’s a layer of mental overhead that’s doing nothing toward actually increasing the value or functionality of the software.

Maintainability is the sort of an extension of comprehensibility - how easy is it the code to change or fix down the road? Maintainability includes things like the “open to extension, closed to modification” principle from SOLID, but also things like comments (which we’ll get to, specifically, later on). Comprehensibility is focused on the “what” the code is doing, which often requires in-code context and clear naming. Maintainability on the other hand, focuses on the “why” - so that, if I need to modify it later on, I know what the intent of the method/class/variable was, and can adjust accordingly.

The single most important aspect of CPM code is naming things. Naming stuff right is hard. How we name things influences how we reason about them, how we classify them, and how others will perceive them. Because those names eventually evolve to carry meaning on their own, which can be influenced by outside contexts, and that whole messy ball of definition is what the next person is going to be using when they think about the thing.

I do believe most programmers intellectually know the importance of naming things, but it’s never given the proper level of respect and care its importance would suggest. Very rarely do I see code reviews that suggest renaming variables or methods to enhance clarity - basically, the rule is if it’s good enough that the reviewer understands it at that moment, that’s fine. I don’t think it is.

A class called User should contain all the methods related to the User model. This seems like an uncontroversial stance. But you have to consider that model in the context of its overall codebase. If there is (and there should be) also a class called Authorization in that codebase, there are already inferences we should be able to draw simply from the names of those two things.

We should assume User and Authorization are closely related; I would assume that some method in Authorization is going to be responsible for verifying that the user of the application is a User allowed to access parts of the application. I would assume these classes are fairly tightly coupled in some respects, and it would be difficult to use one without the other, in some respect.

Names provide signposts and architecture hints of the broader application, and the more attuned to them you are (as both a writer and reader of code), the more information will be able to be conveyed simply by paying attention to them.

If naming is the single most important aspect of CPM, the single most important aspect of naming things is consistency. I personally don’t care about most styling arguments (camelCase vs. snake_case, tabs vs. spaces, whatever). If there’s a style guide for your language or framework, my opinion is you should follow it as closely as possible, deviating only if there’s an actual significant benefit to doing so.

Following style conventions has the two advantages: allowing for easier interoperability of code from different sources, and enabling the use of linters and formatters.

Code is easier to share (both out to others and in from others) if they use same naming conventions and styles, because you’re not adding an extra layer of reasoning atop the code. If you have to remember that Library A uses camelCase for methods but Framework B uses snake_case, that’s however large a section of your brain that is focusing on something other than the logic of what the code is doing.

And enabling linters and formatters means there’s a whole section of code maintenance you no longer have to worry about - you can offload that work to the machine. Remember, computers exist to help us solve problems and offload processing. A deterministic set of rules that can be applied consistently is literally the class of problems computers are designed to handle.

Very broadly, my approach to subjective questions is: Be consistent. Anything that doesn’t directly impact comprehensibility is a subjective decision. Make a decision, set your linter or formatter, and never give another thought to it. Again, consistency is the most important aspect of naming.

But a critically under-appreciated aspect of naming is the context of the author. Everyone sort of assumes we all share the same context, in lots of ways. “Because we work on the same team/at the same company, the next developer will know the meaning of the class PayGrimples.” That may be very broadly true, in that they’ve probably heard of PayGrimples, but it doesn’t mean they share the same context.

A pop-culture example of this is pretty easy - think of the greatest spaceship pilot in the universe, one James Tiberius Kirk. Think about all his exploits, all the strange new worlds he’s discovered. Get a good picture of him in your head.

Which one did you pick? Was it The Original Series’ William Shatner? The new movies’ Chris Pine? Or was it Strange New Worlds’ Paul Wesley?

You weren’t wrong in whatever you picked. Any of those is a valid and correct answer. But if we were talking about Kirk in conversation, you likely would have asked to clarify which one I meant. If we hadn’t, we could talk about two entirely different versions of the same concept indefinitely until we hit upon a divergence point when one of us realized.

Code has that same issue, except whoever’s reading it can’t ask for that clarification. And they can only find out they’re thinking about a different version of the concept if they a) read and digest the code in its entirety before working on it, or b) introduce or uncover a bug in the course of changing it. So when we name things, we should strive for the utmost clarity.

⛔ Unclear without context

type User = { id: number; username: string; firstName: string; lastName: string; isActive: boolean; }

The above is a very basic user model, most of whose properties are clear enough. Id, username, firstName and lastName are all pretty self-explanatory. But then we get to the boolean isActive.

This could mean any number of things in context. They include, but are not limited to:

-

The user is moving their mouse on the screen right now

-

The user has a logged-in session

-

The user has an active subscription

-

The user has logged in within the last 24 hours

-

The user has performed an authenticated activity in the last 24 hours

-

The user has logged in within the last 60 days